Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

NPs can be taught to do GP work: Let’s have conversations not an identity crisis about our roles

NPs can be taught to do GP work: Let’s have conversations not an identity crisis about our roles

Those who started their career as nurses can be taught complexity and, if done well, should be able to perform at the same level as GPs, writes Lucy O’Hagan

Interesting conversations have emerged since publication of my opinion piece in support of independent nurse practitioners in primary healthcare.

All the GPs I have interacted with, on multiple forums, have been appreciative of the NPs they work with, and the lifeline they provide in terms of workforce.

Some GPs hadn’t realised that NPs have legal authority, under the Health Practitioners Competency Assurance Act 2003, to work independently in the same role as GPs. The idea of NPs working without GP supervision was a sticking point for some GPs.

But there is a huge range of views. Some GPs see independent NPs as an important workforce in addressing the health inequities that persist under a traditional general practice model. One young GP said, “I think GPs are having an identity crisis and it will be fun to see where it goes.” We sure need the enthusiasm of the young.

I want to develop my assertion that NPs can be taught to do the role of GPs; many already are doing it. But first we need to describe what GPs actually do.

Recently I have observed a profound sense of GPs feeling undervalued, both by secondary care and funders. Personally, I don’t care what secondary care people think of GPs. I care about what patients think and whether they leave my room feeling better. I care what funders think because primary healthcare is, overall, underfunded.

Our value is in what is unseen, in the consulting room where important things happen, that make a huge difference to people’s outcomes

I have spent much of my career thinking about, and trying to articulate, the value of general practice. First, our worth is not represented in quality measures or performance targets. Nor can our value be easily compared with that of secondary care specialists, because our role and philosophical position differ from theirs. Our value is in what is unseen, in the consulting room where important things happen, that make a huge difference to people’s outcomes.

Recently a fourth-year medical student captured it: “Watching a GP consult was like [watching] someone spin magic.”

I’m sure many other health practitioners, including nurses, also spin magic, but general practice is unique within the medical paradigm, in that we see relationship as a therapeutic element, we are interested in the patient’s whole context, and we integrate medicine and story.

Some consultations are all about the medicine and in others there is only an unwell story, but mostly they are woven intricately together. This work has incredible value and takes great skill.

READ MORE:

My second observation is that general practice is regularly described as becoming more “complex”. We need to define this complexity, so we can explain what we do, and what is required to teach this to both NP and GP trainees.

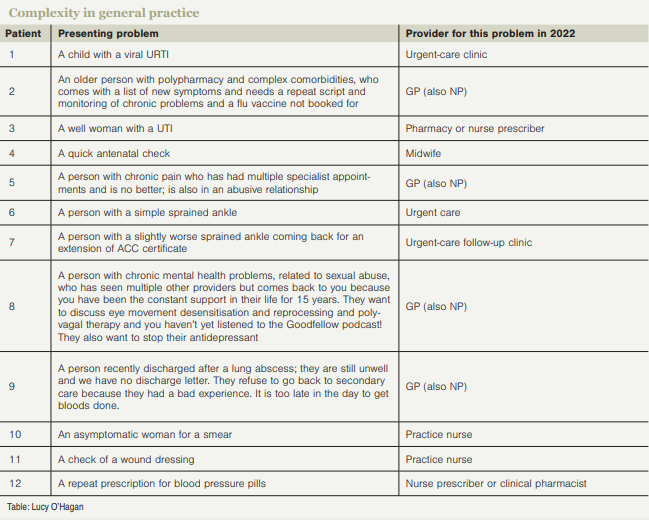

The proportion of complex consultations has increased hugely in my career. Twenty-five years ago, a morning of general practice might have consisted of seeing the 12 patients described in the table (at right).

In 2023, eight of the less complex ones would be seen by another provider. GPs (and now NPs) are left with 12 of the most complex cases. We cannot make primary healthcare more sustainable and desirable when we are expected to do more in less time.

I have been teaching GP registrars for two decades and currently I observe GP registrars do around 100 to 150 consultations a year (with patients, actors or in role plays). I have thought a great deal about the consultations I observe and teach, and I will now attempt to break down the complexity into skills.

I am going to bring NPs back into the whakaaro because I believe those who started their career as nurses can be taught this complexity and, if done well, should be able to perform at the same level as GPs. (I might add that NPs will no doubt bring other skill sets into the room. They may also define the role differently, but I am referring to the role GPs currently perform.)

I have frequently observed that without attention to relationship, the medical parts of the consultation do not go well. Bringing themselves into the consultation can be unnerving for GP registrars. As nursing starts with an ethos of care, I would expect NPs to contribute a lot to our understandings of provider/patient relationship.

As generalists, we need a huge pool of diagnoses and treatments in our heads; the common ones and the less common ones. We need to know what a branchial cleft cyst is, Kawasaki disease, Meckel’s diverticulum and Bechet’s disease, even though we may never see a case of these in our careers.

To be safe, we need to reduce the things we don’t know that we don’t know.

Nurses aren’t necessarily trained in the rarer differentials, but these can be learned (just as medical students learn them). We have HealthPathways to standardise management, and increasingly we will all be using software or even AI to assist with differential diagnosis.

In primary healthcare, diagnostic uncertainty is huge because patients can present early in a serious disease – their symptoms may never reach threshold for a biomedical diagnosis, and we don’t have direct access to a range of investigations. It takes a lot of practice to back our judgement in the face of uncertainty and respond with a safe plan and tempered reassurance.

Safety netting is part of the skilled response to diagnostic uncertainty. Commonly, GP registrars perceive the patient as not particularly sick, so they don’t do a formal differential diagnosis and as a result can struggle with specific safety netting.

For example, you have a patient with one red eye that isn’t too sore, with no visual loss. You must think about serious differentials such as early iritis or dendritic ulcer, because these change the safety net from, “Come back next week if not better” to “I’ll see you tomorrow but if it gets worse overnight go to ED”.

NPs can learn this and as experienced health practitioners they may learn it faster than medical students.

In general practice, there is usually more than one problem per consultation. The patient will have their own list, there will be chronic health problems to monitor, something will come up mid-consult, and then there is the computer’s list of recalls and preventive care.

GP registrars find this overwhelming in 15 minutes, and I imagine NP trainees would too. It takes quite a bit of skill to quickly prioritise the medical problems, negotiate the patient’s priorities and be flexible enough to reprioritise as the consultation proceeds.

In one 15-minute consultation, there may be four to six things that need diagnosis. The patient might have chest pain, a sore toe, a skin spot; you may observe the gait is unsteady, the mood is low. Not everything can be fully assessed, so the skill is to do rapid assessments and to safety-net.

It takes practice to decide whether the unsteady gait and low mood are today’s problem or not. And then there is the skill of noticing that perhaps the real problem is not even being spoken about.

Symptoms we can’t medically explain are a huge part of general practice and this is poorly taught in medical training. For GP trainees, we must shift the focus from a purely biomedical lens to a more holistic one directed at wellbeing. It is possible that NP trainees are moving in the opposite direction, from a holistic wellbeing lens to a biomedical one. It would be an interesting interdisciplinary conversation.

I sense that a huge skill in general practice is pragmatism and problem-solving; working out the most efficient way to get something done. This doesn’t necessarily come naturally to anyone, but we may find nurses are pretty good at it.

GP registrars struggle with the inequities they observe in healthcare. Learning to advocate for and support patients who have barriers to care is a huge learning need for the whole workforce.

All of this takes time to learn. It takes practice. You need to do a lot of it, and to have expert advice and teaching. But registrars learn it and so can NPs.

NPs may want and need a longer training, to feel really confident and safe practising independently. It seems bizarre that NP training is much shorter than GP training. I hope the funders don’t see NPs as cheap to train and cheap to employ. None of us should accept this; it devalues all of our roles.

Ideally, after the NP intern year, learning the skills of a biomedical approach, NPs would enter a three-year fellowship similar to GP registrars, with interprofessional teaching between GP and NP trainees.

We have much to learn from each other.

Conversations need to be happening between the professions at multiple levels.

If we value the contribution, depth of knowledge and experience GPs bring to primary care, and further support NPs while they transition into that role, there is no reason why we can’t all be valued by secondary care, the funders and, most importantly, the people who come to see us.

Lucy O’Hagan is a medical educator and specialist GP working in the Wellington region

We're publishing this article as a FREE READ so it is FREE to read and EASY to share more widely. Please support us and the hard work of our journalists by clicking here and subscribing to our publication and website

![Doctor and nurse [NCI on Unsplash]](/sites/default/files/styles/cropped_image_4_3/public/2023-02/Doctor_and_Nurse_cropped_national-cancer-institute_unsplash.jpg?itok=glnuxTKA)

![Barbara Fountain, editor of New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and Paul Hutchison, GP and senior medical clinician at Tāmaki Health [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20editor%20of%20New%20Zealand%20Doctor%20Rata%20Aotearoa%2C%20and%20Paul%20Hutchison%2C%20GP%20and%20senior%20medical%20clinician%20at%20T%C4%81maki%20Health%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=-HbQ1EYA)

![Lori Peters, NP and advanced health improvement practitioner at Mahitahi Hauora, and Jasper Nacilla, NP at The Terrace Medical Centre in Wellington [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/2.%20Lori%20Peters%2C%20NP%20and%20advanced%20HIP%20at%20Mahitahi%20Hauora%2C%20and%20Jasper%20Nacilla%2C%20NP%20at%20The%20Terrace%20Medical%20Centre%20in%20Wellington%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=sUfbsSF1)

![Ministry of Social Development health and disability coordinator Liz Williams, regional health advisors Mary Mojel and Larah Takarangi, and health and disability coordinators Rebecca Staunton and Myint Than Htut [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/3.%20Ministry%20of%20Social%20Development%27s%20Liz%20Williams%2C%20Mary%20Mojel%2C%20Larah%20Takarangi%2C%20Rebecca%20Staunton%20and%20Myint%20Than%20Htut%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=9ceOujzC)

![Locum GP Helen Fisher, with Te Kuiti Medical Centre NP Bridget Woodney [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/4.%20Locum%20GP%20Helen%20Fisher%2C%20with%20Te%20Kuiti%20Medical%20Centre%20NP%20Bridget%20Woodney%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=TJeODetm)

![Ruby Faulkner, GPEP2, with David Small, GPEP3 from The Doctors Greenmeadows in Napier [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/5.%20Ruby%20Faulkner%2C%20GPEP2%2C%20with%20David%20Small%2C%20GPEP3%20from%20The%20Doctors%20Greenmeadows%20in%20Napier%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=B0u4wsIs)

![Rochelle Langton and Libby Thomas, marketing advisors at the Medical Protection Society [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/6.%20Rochelle%20Langton%20and%20Libby%20Thomas%2C%20marketing%20advisors%20at%20the%20Medical%20Protection%20Society%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=r52_Cf74)

![Specialist GP Lucy Gibberd, medical advisor at MPS, and Zara Bolam, urgent-care specialist at The Nest Health Centre in Inglewood [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/7.%20Specialist%20GP%20Lucy%20Gibberd%2C%20medical%20advisor%20at%20MPS%2C%20and%20Zara%20Bolam%2C%20urgent-care%20specialist%20at%20The%20Nest%20Health%20Centre%20in%20Inglewood%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=z8eVoBU3)

![Olivia Blackmore and Trudee Sharp, NPs at Gore Health Centre, and Gaylene Hastie, NP at Queenstown Medical Centre [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/8.%20Olivia%20Blackmore%20and%20Trudee%20Sharp%2C%20NPs%20at%20Gore%20Health%20Centre%2C%20and%20Gaylene%20Hastie%2C%20NP%20at%20Queenstown%20Medical%20Centre%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=Z6u9d0XH)

![Mary Toloa, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service in Wellington, Mara Coler, clinical pharmacist at Tū Ora Compass Health, and Bhavna Mistry, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/9.%20Mary%20Toloa%2C%20Porirua%20and%20Union%20Community%20Health%20Service%20in%20Wellington%2C%20Mara%20Coler%2C%20T%C5%AB%20Ora%20Compass%20Health%2C%20and%20Bhavna%20Mistry%2C%20PUCHS%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=kpChr0cc)