Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

Misunderstood: Delta drama for family of 55

Misunderstood: Delta drama for family of 55

A Samoan aiga (family), spread across west and central Auckland, tells Alan Perrott about being trapped in a COVID-19 outbreak. It felt like they were battling the health system as much as the virus

It’s not like we’re the first Samoans to end up in hospital

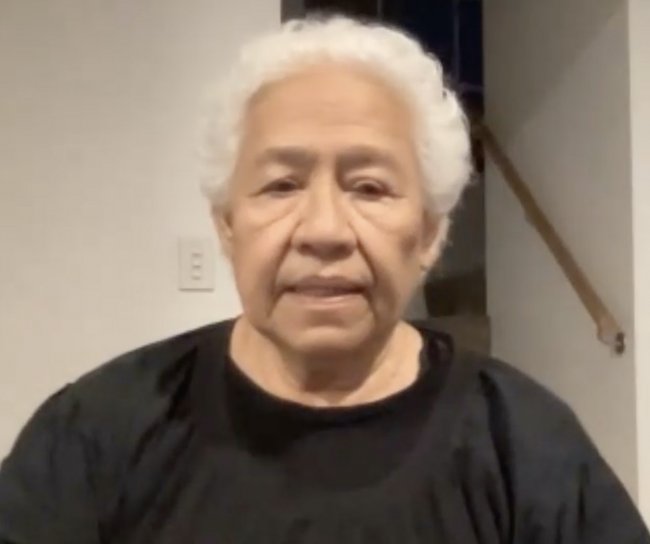

Aniva Epati’s bitter laugh can’t hide her anger.

“There were a lot of issues,” she says, “stuff that the people at the top don’t understand. We poor people go in there and we face the drama. I would tell them all off: ‘Get out of the job, you are useless.’ Ha.”

Known to all as Auntie, the 79-year-old is a matriarch of the wider Epati family, 55 people in eight households spread across west and central Auckland. All were caught up in the Assembly of God COVID-19 subcluster in August.

People from three of the family’s households attended the multi-congregational service in Māngere that has resulted in more than 800 positive cases and one death.

If the consequences for the family had been restricted to the vagaries of the virus’ Delta variant – 12 of the 55 eventually tested positive – the family might not be feeling so angry.

“Systemic problems, racism, there’s a lot there, you know?” says Christina Epati, the oldest of eight siblings.

“I didn’t expect it to happen to us, but it did, and thank goodness we had the support of our whole aiga (family). If we didn’t have that, I don’t know what direction we would have taken.”

The family feels like they were battling the health system as much as the virus and, after dealing with poor communication, failed assurances, incoherent contact tracing, cultural ignorance, and one false negative, they want to share their story in the hope of prompting improvements.

This story is the result of two Zoom meetings between the family and New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa.

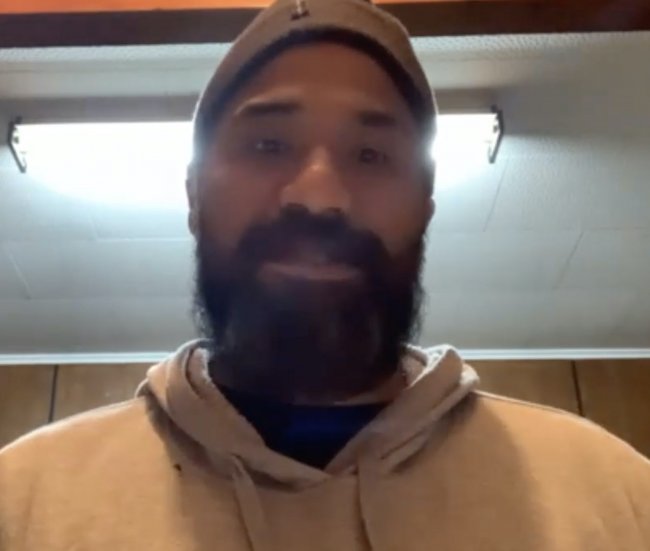

Christina Epati’s nephew, Vaaiga Autagavaia, is a GP at Ōtara Family and Christian Health Centre. Dr Autagavaia says it was “probably pure luck” his elderly relatives did not suffer more serious outcomes, and he found watching the process unfold was “disappointing, frustrating and saddening, all at once”.

He is incredulous the system continues to struggle with Pacific peoples despite the lessons that should have been learned from previous lockdowns.

“A crisis shouldn’t be an excuse. A crisis should give you even more reason to make sure every patient right is upheld. So, this experience has been hard to watch for everyone, but speaking as someone who is passionate about equity and social justice, it’s not surprising.

“But if this is the baseline for the care we can expect,” says Dr Autagavaia, “and it’s only a few months ago that this happened, what does that mean as we move to a community-based approach to managing COVID?

“This is what GPs have been saying, that we were running on fumes before the pandemic, so how is it that we, all of a sudden, are going to fill the tank up again and go above and beyond from here?

“It’s not that GPs don’t want to try, that primary care doesn’t want to try, but we just know that to meet the needs of our families, just as it has been told by my family, it’s going to be a real struggle.”

Both of Christina Epati’s parents, Pelesala and Fuisa Epati, contracted COVID-19 after attending the service at Māngere’s Assembly of God church on 15 August, just before New Zealand moved to Alert Level 4.

Both quickly became unwell; her father had to be admitted into North Shore Hospital before their positive test results were confirmed.

Despite all the sudden attention from health agencies, the language barriers and lack of information meant they struggled to understand what was happening.

“From getting tests done, the anxiety, the not knowing what to expect, not knowing what was happening to them physically, the numerous phone calls from people from different health agencies asking them the same repetitive questions: it was difficult for them, especially when they were feeling unwell,” says Christina Epati, the couple’s eldest daughter.

“We weren’t being told anything, and they started to fret about whether or not they were going to be picked up. They waited for days and their health was deteriorating. My dad was making us ring the ambulance to just come and do checks on them, because he was really worried about his heart and his breathing. Yeah, it was massive.”

A few hours after they made it to a managed isolation and quarantine centre, Christina was called by the facility’s interpreter to say their mother was unwell.

“He told us he was having to push the staff to get her to hospital, which was disheartening.” But she says it was also a relief, as they knew their parents would be reluctant to ask for help.

Her father’s health then declined rapidly as they awaited the ambulance, so they were both picked up and were to be taken to different hospitals, until the family intervened and argued for their parents to be kept together at Middlemore Hospital.

At the same time, the Epati aiga were looking online for information. Christina managed to reach a friend, a nurse who could explain COVID-19 in more detail. Health officials had until now offered nothing but instructions, and the parents were feeling anxious.

She managed to call her father and explained, in Samoan, what he could expect to feel, the likelihood of severe breathing problems, and not to panic.

“If we hadn’t been able to communicate that message, I don’t know if he would still be here with us. We’re not medical, we don’t have that background, we were only going off what people were sharing with us, but we had to find it out for ourselves.”

The family are grateful for the help provided by Middlemore staff, but say it was still another week before Mr and Mrs Epati were provided with an interpreter and could speak to their family.

Meanwhile, Christina’s brother, Matty Epati, back in New Zealand after living in Australia, had been exhibiting COVID-19 symptoms while bedridden with gout. He was assured a mobile unit would be sent to test him and his niece, but it took three days to arrive.

Matty Epati says this had become a pattern. He suggests that, “if you say you are going to do something, then do it”.

After testing positive, he was told by MIQ staff to share a room with his niece, a suggestion the family rejects as culturally inappropriate.

“I’d told them we needed separate rooms, so I stood in the corridor and said ‘no, I’m, not going in that room. You can either get us separate rooms like I asked, or you can take me back home’.”

By now the subcluster had exceeded 100 cases and the family was feeling the stress, to the point of feeling harassed by the contact tracers.

“They were ringing one family who had seven kids seven times,” says Christina Epati.

“Another sister has got the five children, her, an elderly mum and hubby, and she was being called eight times from eight different people contact tracing, and she’s a young mum you know, she’s like, what is going on?”

The process mystified the extended family; some households who they thought would be close contacts weren’t being called at all.

And the outbreak continued to grow.

Tali Meavale, who lives with his 74-year-old mother, was a close contact and had been self-isolating in his room. On the morning of 25 August, Mr Meavale was called and informed his test was negative.

“Then I opened my door to my mum, and we went shopping. We went to PAK’nSAVE, Countdown and the dairy then we came back home, and then they called again and said, ‘oh, sorry, you tested positive’ – after I’d put my mum at risk, all those workers at risk.”

Mr Meavale was asked if he could make his own way to MIQ but, worried about the possibility of infecting others, he asked to be picked up. Despite being a known positive case in the community, he was not taken to MIQ for another four days.

He stuck to his room as much as possible, but still had to share the bathroom, toilet and kitchen with his mother, who was not ill and was being regularly tested.

He arrived at MIQ on 29 August. On his third day, his mother’s sixth test returned a positive result and she immediately joined him.

Mr Meavale kept himself busy posting brief Samoan-language cartoons that help explain the illness and what happens if you become infected.

His (and Christina’s) aunty, Aniva Epati and her daughter Lillyan also arrived at MIQ on 29 August but, while her nephew was enjoying the peace and quiet, she was feeling forgotten. Aside from the morning call to check on their symptoms, she says no one checked to see if they were okay.

She says they were given no information on what was happening to them, or what to expect if she got ill.

They had done nothing wrong, but she says it felt like prison.

As for exercise: “When it’s raining, they ring: ‘do you want to go for a walk?’ When it’s fine, they don’t ring. That’s a good trick.”

Another of Christina’s sisters, Janice Epati, was pregnant when she tested positive. The risk of pneumonia saw her spend three days in hospital, but not before the humiliation of having to strip down and put on PPE gear in the car park in front of staff.

“It’s not like we’re the first Samoans to end up in hospital,” says Christina Epati.

Their situation began to change after Aniva Epati expressed her frustrations on Newshub’s 6pm television news on 28 August, the day before she entered managed isolation.

The interview was seen by the Epatis’ second cousin, Apulu Uta’ile’uo Tu’u’u Mary Kalala Autagavaia, who then contacted son Dr Autagavaia and the rest of the family network.

“That’s how we all came on board to support the family,” says Dr Autagavaia.

“It’s like at Samoan funerals, when someone passes away, everyone rallies, everyone comes with their resources to lift that family up in their time of need.”

The Epati sisters had begun mapping out the movement of every member of the eight households in their aiga.

They also hosted daily Zoom talanoa (discussion) sessions, which identified another nine people who had attended the service.

A cousin, Osana Kirisome, mapped the data they used to identify the infection pathway while another of the Epati sisters, Maylene Epati-Tibbotts, became fact checker. She would collect any questions and comments that might arise and then return with accurate information at the next Zoom meeting.

By 2 September, their subcluster was contained, with everyone understanding the need to get tested and isolate.

“One of the main take aways from this,” says Christina Epati, “is what happens when you empower families to find solutions.” She cites a Samoan proverb: “E fofo le alamea le alamea”, a metaphor for the ability of communities to solve their own problems.

The family had also reached out to influential Samoans within the health system, and were talking regularly to Ministry of Health director, Pacific, Gerardine Clifford-Lidstone, Counties Manukau DHB chief executive Fepulea’i Margie Apa and MIQ clinical nurse director Pauline Fuimaona Sanders.

South Seas Healthcare chief executive Silao Vaisola-Sefo then came on board to provide ongoing care and welfare support.

Which, while welcome, is also a concern, says Dr Autagavaia. Theirs is a high-functioning aiga and they still struggled, he says, so how about all the other Pacific and Māori whānau caught up in the outbreak?

Families in emergency housing and precarious living conditions, and gang families, probably don’t have the resilience or the capability his family has had, “to draw on resources and have the ability to trouble-shoot it for ourselves”.

“So, it is no surprise the Government and Ministry of Health have struggled to engage those people.

“But I want to speak strongly for our family. What has been done is a testament – even though the health system has been a disappointment in so many ways – to its strengths, and that is something the health system fails to grasp.

“Those strengths are probably the key to some of those long-standing challenges to engage with Pacific people,” Dr Autagavaia says.

The extra help didn’t mean their problems were over.

Pelesala and Fuisa Epati were discharged from Middlemore Hospital after two weeks, but Mr Epati’s health declined again a few days later.

Christina Epati says six calls for help failed to reach anyone, so South Seas sent nurse Cherry Elisaia’s Ōtara-based mobile team to west Auckland.

Ms Elisaia says Mr Epati needed emergency treatment. After advising his family GP at Ranui Medical Centre, she made three calls to North Shore Hospital – to the operational manager, duty manager and charge nurse – to warn them they were on their way and to have an interpreter on hand as the patient was distressed.

No interpreter was ever provided during Mr Epati’s stay; the hospital also had incorrect contact details for his family.

Says Tiana Epati: “It’s been pretty dramatic, considering it’s not like we’ve just arrived in the country. Our parents have contributed for 50 years, you know? We deserve care too, and we deserve to be treated like humans, not bloody stock.”

New Zealand Doctor has received responses to this aiga’s story from providers involved in their care.

Counties Manukau DHB communications portfolio lead Michael Hennessy says the lessons learned during the Delta outbreak are being shared with other DHBs.

“We all need to ensure there is a focus on providing regular updates to families regarding the status of loved ones,” Mr Hennessy says. “We also need to remind ourselves that we will need to adapt and respond to the heightened anxiety all patients and their families will be feeling about COVID-19 and ensure we have processes in place that can deal with any language difficulties we might experience.”

South Seas Healthcare Wellbeing Hub team lead Ana Rogers says the family’s agitation was understandable.

“We found that language barriers and differing translations in messaging around isolation played a big part in delayed information. The MIQ/self-isolation system is a difficult system to navigate…[The Auckland Regional Public Health Service] have a general message for the whole population and then specific messages for individual families – which is hard for families to comprehend.

“Conversations amongst themselves also caused problems with misinformation being spread. Through our care plans and talanoas, we were able to hear the stories of those impacted by this and connect appropriately.”

Counties’ boss Ms Apa, who is also Northern Region Health Coordination Centre lead, says the need to respond swiftly to the Delta outbreak caused “inconsistent experiences”, and apologies have been provided.

She says the contact-tracing system now takes a whānau whakapapa approach, which sees cases and contacts in a wider context. A Pae Ora mobile unit has been created to manage cases, undertake testing and provide manaaki support, so whānau can remain in isolation.

Large Pacific households are now being assisted by the public health service’s Pasifika case-management and contact-tracing team. Ms Apa says it features cultural support, interpreters and church ministers’ wives, who wrap support around households.

Cases and contacts are now mapped according to family connections so all family members, and church or other gatherings can be seen in their entirety.

Transfers to MIQ are managed case-by-case following a risk assessment, Ms Apa adds. She says the Pae Ora team discusses what home isolation will mean for each individual and their wider whānau, especially if there could be difficulty keeping physical distance in the home.

“Large households face extended isolation, as it is likely that more members will test positive, so the Pasifika team have culturally appropriate discussions and work collaboratively with all family members to determine the best options on isolating at home or off-site in a managed isolation facility.

“Home isolation is playing an increasingly important role in supporting the health system to better manage COVID-19 cases in the community, and this will reduce the need for transfers to MIQ,” Ms Apa says.

![Barbara Fountain, editor of New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and Paul Hutchison, GP and senior medical clinician at Tāmaki Health [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20editor%20of%20New%20Zealand%20Doctor%20Rata%20Aotearoa%2C%20and%20Paul%20Hutchison%2C%20GP%20and%20senior%20medical%20clinician%20at%20T%C4%81maki%20Health%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=-HbQ1EYA)

![Lori Peters, NP and advanced health improvement practitioner at Mahitahi Hauora, and Jasper Nacilla, NP at The Terrace Medical Centre in Wellington [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/2.%20Lori%20Peters%2C%20NP%20and%20advanced%20HIP%20at%20Mahitahi%20Hauora%2C%20and%20Jasper%20Nacilla%2C%20NP%20at%20The%20Terrace%20Medical%20Centre%20in%20Wellington%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=sUfbsSF1)

![Ministry of Social Development health and disability coordinator Liz Williams, regional health advisors Mary Mojel and Larah Takarangi, and health and disability coordinators Rebecca Staunton and Myint Than Htut [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/3.%20Ministry%20of%20Social%20Development%27s%20Liz%20Williams%2C%20Mary%20Mojel%2C%20Larah%20Takarangi%2C%20Rebecca%20Staunton%20and%20Myint%20Than%20Htut%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=9ceOujzC)

![Locum GP Helen Fisher, with Te Kuiti Medical Centre NP Bridget Woodney [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/4.%20Locum%20GP%20Helen%20Fisher%2C%20with%20Te%20Kuiti%20Medical%20Centre%20NP%20Bridget%20Woodney%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=TJeODetm)

![Ruby Faulkner, GPEP2, with David Small, GPEP3 from The Doctors Greenmeadows in Napier [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/5.%20Ruby%20Faulkner%2C%20GPEP2%2C%20with%20David%20Small%2C%20GPEP3%20from%20The%20Doctors%20Greenmeadows%20in%20Napier%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=B0u4wsIs)

![Rochelle Langton and Libby Thomas, marketing advisors at the Medical Protection Society [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/6.%20Rochelle%20Langton%20and%20Libby%20Thomas%2C%20marketing%20advisors%20at%20the%20Medical%20Protection%20Society%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=r52_Cf74)

![Specialist GP Lucy Gibberd, medical advisor at MPS, and Zara Bolam, urgent-care specialist at The Nest Health Centre in Inglewood [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/7.%20Specialist%20GP%20Lucy%20Gibberd%2C%20medical%20advisor%20at%20MPS%2C%20and%20Zara%20Bolam%2C%20urgent-care%20specialist%20at%20The%20Nest%20Health%20Centre%20in%20Inglewood%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=z8eVoBU3)

![Olivia Blackmore and Trudee Sharp, NPs at Gore Health Centre, and Gaylene Hastie, NP at Queenstown Medical Centre [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/8.%20Olivia%20Blackmore%20and%20Trudee%20Sharp%2C%20NPs%20at%20Gore%20Health%20Centre%2C%20and%20Gaylene%20Hastie%2C%20NP%20at%20Queenstown%20Medical%20Centre%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=Z6u9d0XH)

![Mary Toloa, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service in Wellington, Mara Coler, clinical pharmacist at Tū Ora Compass Health, and Bhavna Mistry, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/9.%20Mary%20Toloa%2C%20Porirua%20and%20Union%20Community%20Health%20Service%20in%20Wellington%2C%20Mara%20Coler%2C%20T%C5%AB%20Ora%20Compass%20Health%2C%20and%20Bhavna%20Mistry%2C%20PUCHS%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=kpChr0cc)