Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

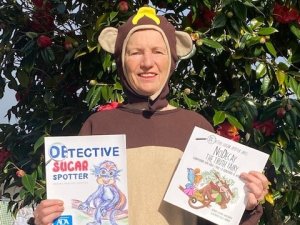

On a mission to save children’s teeth

On a mission to save children’s teeth

Here at New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa we are on our summer break! While we're gone, check out Summer Hiatus: Stories we think deserve to be read again! This article was first published on 14 September 2022.

Chosen by Maia Hall: Breakthrough research on dental ‘remineralisation’ has established a research base, and set Fijian expert Jason Nath on a mission to improve child dental health in the Pacific

Remineralisation would lower the level of invasive care required, but only if the decay can be caught in time

A Fijian dentistry expert studying in New Zealand has advanced global understanding of how to reverse tooth decay.

In 2019, Jason Nath travelled from Fiji to Dunedin to complete his clinical doctorate at the University of Otago on a three-year Manaaki New Zealand scholarship.

Specialising in paediatric dental health, his doctoral research focused on self-assembling peptides to reverse enamel damage before it requires invasive treatment.

Dr Nath used peptides on artificially decayed teeth to form a “scaffold”. When ions such as phosphates and calcium were reintroduced to these partially demineralised teeth, they could more easily grab hold of the scaffold, which enhances remineralisation.

Teeth start to lose mineral content when the mouth’s pH level reaches a level of acidity. A neutral pH in the mouth is between 7.2 and 7.1, Dr Nath says.

Demineralisation occurs when the pH level falls lower than 5.5, “and all the calcium and phosphate ions start to escape the enamel”.

Remineralisation occurs naturally when teeth are appropriately cared for; but Dr Nath’s research proves it can also be performed artificially to aid tooth repair and harden enamel.

He says the remineralisation technique would lower the level of invasive care required, but only if the decay can be caught in time.

Before receiving the Manaaki scholarship, Dr Nath was a qualified dentist and assistant lecturer at the School of Dentistry and Oral Health at Fiji National University.

He had no formal postgraduate training in dentistry but, while he was teaching, he obtained postgraduate qualifications in public health.

Prospective clinical doctorate students at the University of Otago usually must complete primary exams first but, because Dr Nath had postgraduate qualifications and about nine years of clinical dentistry experience, he was given automatic entry.

After completing the scholarship and returning to Fiji, Dr Nath was promoted to assistant professor.

Back home, he is working to change oral healthcare behaviour, starting with parents and children.

Dental hygiene problems in the Pacific stem from lack of education and resources, he says.

“When a child presents with a mouthful of decay it’s not their fault.”

Given the shortage of dentists in Fiji, Dr Nath says dentists often don’t have time to talk parents through caring for their baby’s teeth, so children don’t build healthy dental habits.

He says the issue affects the whole health sector: “We need nurses and pharmacists and doctors to start talking about teeth.”

Dr Nath says parents need to establish good oral health habits with their children, such as brushing twice a day, avoiding sugary foods and having regular dental check-ups.

Dental fear and anxiety is a real problem: “We need to be positive about going to the dentist. Children are scared, they do not want to go to the dentist. Parents need to introduce them early, not wait until they are in pain and need invasive treatment.”

Parents need to be equipped with an oral health plan before their baby is born, Dr Nath suggests.

“Perhaps during pregnancy check-ups, the nurse could point out developmental milestones for your child’s oral health: when your first dental visits should be scheduled, what you should be feeding the baby, and tips such as not putting your baby to sleep with a bottle.”

As a result of Dr Nath’s work, use of biomimetic remineralisation of early enamel lesions is now a common area of research. Further investigation is under way in the cariology and minimal invasive dentistry experiments programme at the University of Otago, he says.

Dentistry honours student Kerry Chen is running analysis on the remineralisation potential of selected peptides, with Dr Nath as co-investigator.

He says new research in both Fiji and New Zealand is finding huge benefits in regularly drinking fluoridated water to strengthen enamel and bring down the pH level in the mouth. Fluoride makes the enamel more resistant to decay, which means teeth can withstand a more acidic pH level before they start to demineralise.

While the health benefits of drinking water have been widely established, the oral health benefits “from the frequency of drinking water – that’s new”, he says. This is a complicated issue in Fiji, where many communities rely on natural streams and wells which do not have natural fluoride content.

In New Zealand, 14 local authorities were recently directed by the Ministry of Health to fluoridate their water supply, and can apply for a share of $11.3 million allocated for the associated capital projects.

Once these supplies are complete, between 51 and 60 per cent of New Zealanders will have access to fluoridated water, the ministry says in a media release.

![Barbara Fountain, editor of New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and Paul Hutchison, GP and senior medical clinician at Tāmaki Health [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20editor%20of%20New%20Zealand%20Doctor%20Rata%20Aotearoa%2C%20and%20Paul%20Hutchison%2C%20GP%20and%20senior%20medical%20clinician%20at%20T%C4%81maki%20Health%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=-HbQ1EYA)

![Lori Peters, NP and advanced health improvement practitioner at Mahitahi Hauora, and Jasper Nacilla, NP at The Terrace Medical Centre in Wellington [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/2.%20Lori%20Peters%2C%20NP%20and%20advanced%20HIP%20at%20Mahitahi%20Hauora%2C%20and%20Jasper%20Nacilla%2C%20NP%20at%20The%20Terrace%20Medical%20Centre%20in%20Wellington%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=sUfbsSF1)

![Ministry of Social Development health and disability coordinator Liz Williams, regional health advisors Mary Mojel and Larah Takarangi, and health and disability coordinators Rebecca Staunton and Myint Than Htut [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/3.%20Ministry%20of%20Social%20Development%27s%20Liz%20Williams%2C%20Mary%20Mojel%2C%20Larah%20Takarangi%2C%20Rebecca%20Staunton%20and%20Myint%20Than%20Htut%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=9ceOujzC)

![Locum GP Helen Fisher, with Te Kuiti Medical Centre NP Bridget Woodney [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/4.%20Locum%20GP%20Helen%20Fisher%2C%20with%20Te%20Kuiti%20Medical%20Centre%20NP%20Bridget%20Woodney%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=TJeODetm)

![Ruby Faulkner, GPEP2, with David Small, GPEP3 from The Doctors Greenmeadows in Napier [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/5.%20Ruby%20Faulkner%2C%20GPEP2%2C%20with%20David%20Small%2C%20GPEP3%20from%20The%20Doctors%20Greenmeadows%20in%20Napier%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=B0u4wsIs)

![Rochelle Langton and Libby Thomas, marketing advisors at the Medical Protection Society [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/6.%20Rochelle%20Langton%20and%20Libby%20Thomas%2C%20marketing%20advisors%20at%20the%20Medical%20Protection%20Society%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=r52_Cf74)

![Specialist GP Lucy Gibberd, medical advisor at MPS, and Zara Bolam, urgent-care specialist at The Nest Health Centre in Inglewood [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/7.%20Specialist%20GP%20Lucy%20Gibberd%2C%20medical%20advisor%20at%20MPS%2C%20and%20Zara%20Bolam%2C%20urgent-care%20specialist%20at%20The%20Nest%20Health%20Centre%20in%20Inglewood%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=z8eVoBU3)

![Olivia Blackmore and Trudee Sharp, NPs at Gore Health Centre, and Gaylene Hastie, NP at Queenstown Medical Centre [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/8.%20Olivia%20Blackmore%20and%20Trudee%20Sharp%2C%20NPs%20at%20Gore%20Health%20Centre%2C%20and%20Gaylene%20Hastie%2C%20NP%20at%20Queenstown%20Medical%20Centre%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=Z6u9d0XH)

![Mary Toloa, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service in Wellington, Mara Coler, clinical pharmacist at Tū Ora Compass Health, and Bhavna Mistry, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/9.%20Mary%20Toloa%2C%20Porirua%20and%20Union%20Community%20Health%20Service%20in%20Wellington%2C%20Mara%20Coler%2C%20T%C5%AB%20Ora%20Compass%20Health%2C%20and%20Bhavna%20Mistry%2C%20PUCHS%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=kpChr0cc)