Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

Unravelling the link between occupational inhalants and rheumatoid arthritis

Unravelling the link between occupational inhalants and rheumatoid arthritis

We are on our summer break and the editorial office is closed until 17 January. In the meantime, please enjoy our Summer Hiatus series, an eclectic mix from our news and clinical archives and articles from The Conversation throughout the year. This article was first published in the 9 June edition

Occupational health expert David McBride looks at the association between occupation and rheumatoid arthritis, and highlights the lung as an initial site of inflammation and autoimmunity

- Patients with rheumatoid arthritis can be subdivided on the basis of the presence of anti-citrullinated protein antibodies.

- Different genetic and environmental risk factors are associated with ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative RA.

- In ACPA-positive RA, asymptomatic autoimmunity appears to start in the lungs, and a “second hit” (eg, infection) initiates the transition to inflammatory arthritis.

- Tobacco smoking, silica exposure and inhalant-related occupations are associated with increased risk of RA, particularly ACPA-positive RA.

This article has been endorsed by the RNZCGP and has been approved for up to 0.25 CME credits for the General Practice Educational Programme and continuing professional development purposes (1 credit per learning hour). To claim your credits, log in to your RNZCGP dashboard to record this activity in the CME component of your CPD programme.

Nurses may also find that reading this article and reflecting on their learning can count as a professional development activity with the Nursing Council of New Zealand (up to 0.25 PD hours).

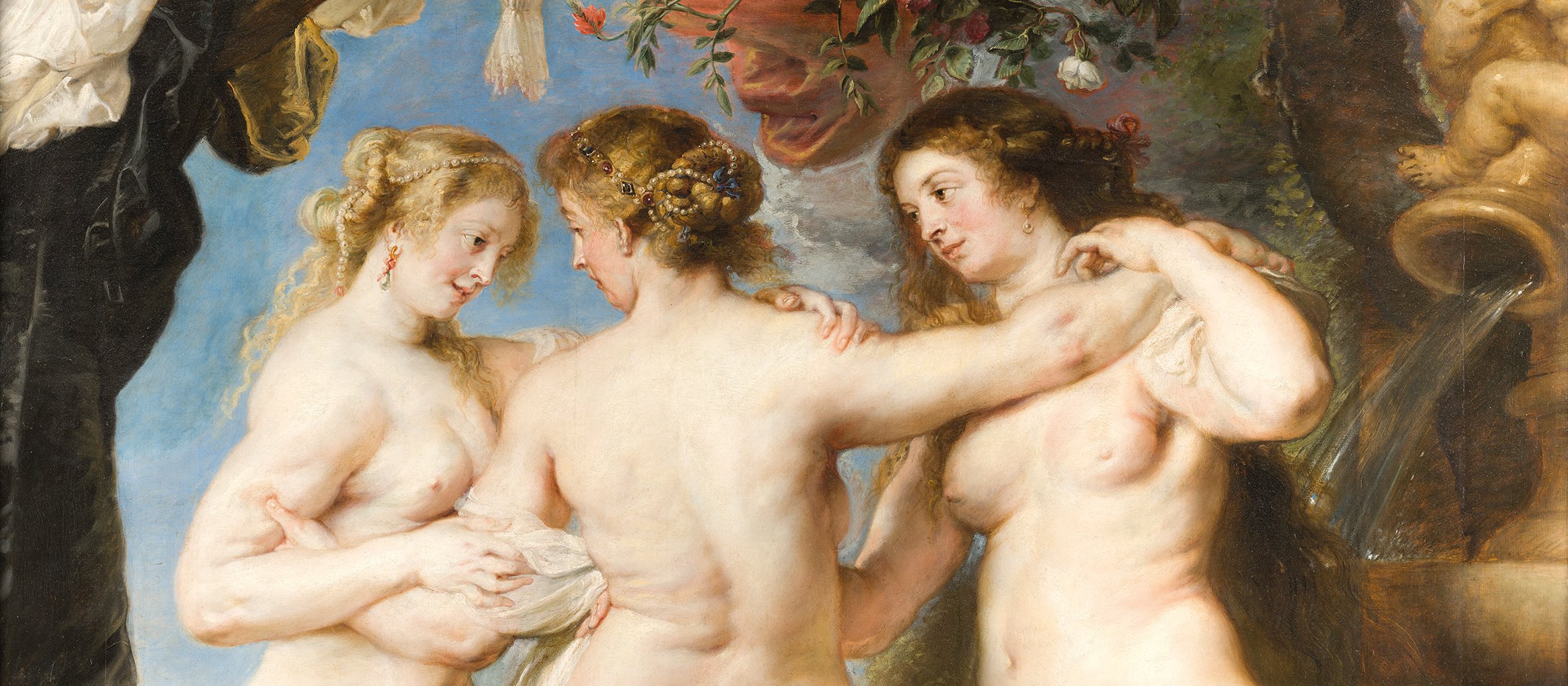

If you look at Peter Paul Rubens’ painting The Three Graces, you will see that the grace on the left has a deformity of the ring and little fingers of the right hand. The distal interphalangeal joints are in hyperextension, which is a position that the hand cannot adopt unless the finger has suffered an accident or is rheumatic – the Boutonnière deformity.

The art historians among you will know that the artist's second wife, Hélène Fourment, was a model for the graces and was age 23 when the painting was completed. Rubens himself also suffered from a “gouty” arthritis of the hands, feet and knees. Rheumatologist Thierry Appelboom, writing in the “Heberden Historical Series” of Rheumatology, hypothesised that in Rubens’ home of Antwerp, in the early part of the 17th century, an infectious agent might have been imported by seafarers returning from the New World, resulting in an “epidemic” of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).1

The best known environmental “finger on the trigger” is smoking tobacco. I became aware of the association through our cohort of 3358 Vietnam veterans, with 25 cases observed and 14.7 expected over the follow-up period, a standardised hospitalisation ratio of 1.70, 95 per cent confidence interval (CI) 1.03–2.36.

The mechanism is a little complex but known to be associated with citrullination of arginine. Citrulline is an amino acid, not coded in DNA, but produced from arginine via post-translational modification.

In RA, and also other autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, citrullinated proteins are targeted by autoantibodies – anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs), assayed in the clinic as anti-cyclic citrullinated peptides (anti-CCP antibody test).

Apart from RA, ACPAs are also found in the cell debris following neuronal destruction in Alzheimer disease, and after smoking tobacco.

The molecular basis arises from the alleles of the HLADRB1 gene – part of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on chromosome 6 – that encode a conserved five amino acid sequence in the third hypervariable region of the HLADR beta chain, known as the “shared epitope”. The SE is involved in presenting antigen to helper T-cells and is associated with RA susceptibility and with the presence of ACPAs in patients with RA.

The point, which I have come to at last, is that ACPApositive RA has a peculiar factor: the citrulline autoimmunity is initiated outside the joints, in the lung, and “primes” the immune system. A “second hit” initiates the transition from asymptomatic autoimmunity to inflammatory arthritis, and that could be from a viral infection, trauma or localised joint inflammation.

ACPA-negative RA has been more difficult to study because the search must be widened beyond the MHC – the associations between the HLA-DRB1 alleles and ACPA-negative RA are much weaker. We are on a hunt for the places in the genome where people differ. We are looking for differences in a single base pair of adenine, cytosine, thymine and guanine, the bonds between which form the “rungs of the ladder” in the DNA double helix. These are single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, most of which occur in non-coding areas and don’t impact on disease risk, but it is important to find the ones that do.

Don’t stop reading, we will keep the momentum going. In the words of the Bard, William Shakespeare, “once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more”.

We now have a mechanism by which an occupational exposure can cause RA. Silica exposure is a case in point. Recent meta-analyses have confirmed the association between occupational silica exposure and RA, as well as the interaction with smoking.2,3 The mechanism is less clear, but it is certainly inflammatory in nature, with release of interleukins, particularly interleukin-1 beta, from pulmonary macrophages.

Having defined the mechanism, what does the epidemiology say, and will it help with risk management?

RA associated with occupation was first mentioned by Snorrason in 1951.4 He examined a total of 573 patients admitted to the Municipal Hospital of Bispebjerg, Copenhagen. The postulate was that RA was a disease of the lower classes of society – it was formerly called arthritis pauperum. Not so. School principals, those in business or the “liberal professions”, barristers, physicians, authors, etc, were just as prone as employees and “workmen”, the latter category including housemaids.

If you remember, epidemiological methods were undergoing development in the 1940s and 1950s. The cohort method, which is good for looking at rare exposures and risk of disease, was being used in cohorts of asbestos workers and “smoking doctors”.

The case-control design is good for finding the cause of disease, which is what they did in the Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis study between 1996 and 2013. In Sweden, almost all cases of RA are referred to a rheumatology unit, and with most of the rheumatology units participating, they ended up with 3973 cases enrolled in the study, along with 7681 controls.

Both cases and controls were asked to answer an extensive questionnaire, comprising questions on heredity, demography, socioeconomics, work history, lifestyle factors, environmental factors and psychosocial factors.

The results were presented by occupation, confirming that airborne exposures may have an effect – bricklayers and concrete workers (odds ratio [OR] 2.9, 95 per cent CI 1.4–5.7), material handling operators (OR 2.4, 95 per cent CI 1.3–4.4), and electrical and electronics workers (OR 2.1, 95 per cent CI 1.1–3.8) all had increased risk of ACPApositive RA.5

Bricklayers and concrete workers (OR 2.4, 95 per cent CI 1.0–5.7) and electrical and electronics workers (OR 2.6, 95 per cent CI 1.3–5.0) had increased risk of ACPA-negative RA. The only risk in women was for assistant nurses and attendants, for ACPA-positive disease (OR 1.3, 95 per cent CI 1.1–1.6).5

A subsequent review added farming, being in the military, scrap recycling and coal mining to the occupations with increased risk for developing RA, all of which are associated with airborne exposures and the latter with silica.6

The learning points here are, as usual, to take an occupational and environmental history in those with suspected RA (systemic upset with muscle and joint pains and stiffness), enquire about a second hit in terms of trauma or viral infection, ask for anti-CCP on the lab form, and get the patient to a rheumatologist with all due speed.

I would say make an ACC claim, but good luck with that. Unlike Rubens, I am graceless.

David McBride is an associate professor in occupational and environmental medicine at Otago Medical School, Dunedin

You can use the Capture button below to record your time spent reading and your answers to the following learning reflection questions:

- Why did you choose this activity (how does it relate to your PDP learning goals)?

- What did you learn?

- How will you implement the new learning into your daily practice?

- Does this learning lead to any further activities that you could undertake (audit activities, peer discussions, etc)?

We're publishing this article as a FREE READ so it is FREE to read and EASY to share more widely. Please support us and our journalism – subscribe here

1. Appelboom T. Hypothesis: Rubens--one of the first victims of an epidemic of rheumatoid arthritis that started in the 16th-17th century? Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44(5):681–83.

2. Morotti A, Sollaku I, Franceschini F, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis on the association of occupational exposure to free crystalline silica and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2021; 2 March online.

3. Mehri F, Jenabi E, Bashirian S, et al. The association between occupational exposure to silica and risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis. Saf Health Work 2020;11(2):136–42.

4. Snorrason E. Rheumatoid arthritis and occupation. Acta Med Scand 1951;140(5):355–58.

5. Ilar A, Alfredsson L, Wiebert P, et al. Occupation and risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis: Results from a population-based case-control study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2018;70(4):499–509.

6. Prisco LC, Martin LW, Sparks JA. Inhalants other than personal cigarette smoking and risk for developing rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2020;32(3):279–88.

![Barbara Fountain, editor of New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and Paul Hutchison, GP and senior medical clinician at Tāmaki Health [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20editor%20of%20New%20Zealand%20Doctor%20Rata%20Aotearoa%2C%20and%20Paul%20Hutchison%2C%20GP%20and%20senior%20medical%20clinician%20at%20T%C4%81maki%20Health%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=-HbQ1EYA)

![Lori Peters, NP and advanced health improvement practitioner at Mahitahi Hauora, and Jasper Nacilla, NP at The Terrace Medical Centre in Wellington [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/2.%20Lori%20Peters%2C%20NP%20and%20advanced%20HIP%20at%20Mahitahi%20Hauora%2C%20and%20Jasper%20Nacilla%2C%20NP%20at%20The%20Terrace%20Medical%20Centre%20in%20Wellington%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=sUfbsSF1)

![Ministry of Social Development health and disability coordinator Liz Williams, regional health advisors Mary Mojel and Larah Takarangi, and health and disability coordinators Rebecca Staunton and Myint Than Htut [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/3.%20Ministry%20of%20Social%20Development%27s%20Liz%20Williams%2C%20Mary%20Mojel%2C%20Larah%20Takarangi%2C%20Rebecca%20Staunton%20and%20Myint%20Than%20Htut%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=9ceOujzC)

![Locum GP Helen Fisher, with Te Kuiti Medical Centre NP Bridget Woodney [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/4.%20Locum%20GP%20Helen%20Fisher%2C%20with%20Te%20Kuiti%20Medical%20Centre%20NP%20Bridget%20Woodney%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=TJeODetm)

![Ruby Faulkner, GPEP2, with David Small, GPEP3 from The Doctors Greenmeadows in Napier [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/5.%20Ruby%20Faulkner%2C%20GPEP2%2C%20with%20David%20Small%2C%20GPEP3%20from%20The%20Doctors%20Greenmeadows%20in%20Napier%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=B0u4wsIs)

![Rochelle Langton and Libby Thomas, marketing advisors at the Medical Protection Society [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/6.%20Rochelle%20Langton%20and%20Libby%20Thomas%2C%20marketing%20advisors%20at%20the%20Medical%20Protection%20Society%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=r52_Cf74)

![Specialist GP Lucy Gibberd, medical advisor at MPS, and Zara Bolam, urgent-care specialist at The Nest Health Centre in Inglewood [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/7.%20Specialist%20GP%20Lucy%20Gibberd%2C%20medical%20advisor%20at%20MPS%2C%20and%20Zara%20Bolam%2C%20urgent-care%20specialist%20at%20The%20Nest%20Health%20Centre%20in%20Inglewood%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=z8eVoBU3)

![Olivia Blackmore and Trudee Sharp, NPs at Gore Health Centre, and Gaylene Hastie, NP at Queenstown Medical Centre [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/8.%20Olivia%20Blackmore%20and%20Trudee%20Sharp%2C%20NPs%20at%20Gore%20Health%20Centre%2C%20and%20Gaylene%20Hastie%2C%20NP%20at%20Queenstown%20Medical%20Centre%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=Z6u9d0XH)

![Mary Toloa, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service in Wellington, Mara Coler, clinical pharmacist at Tū Ora Compass Health, and Bhavna Mistry, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/9.%20Mary%20Toloa%2C%20Porirua%20and%20Union%20Community%20Health%20Service%20in%20Wellington%2C%20Mara%20Coler%2C%20T%C5%AB%20Ora%20Compass%20Health%2C%20and%20Bhavna%20Mistry%2C%20PUCHS%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=kpChr0cc)