Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

Maternal birth injuries

Maternal birth injuries

On 1 October 2022, the Accident Compensation (Maternal Birth Injury and Other Matters) Amendment Act 2022 came into effect, resulting in the biggest change to ACC coverage of injuries in recent history. Now, birthing parents can access ACC funding for maternal birth injuries that were previously excluded from coverage. This article, written by Melissa Davidson, outlines what this means for birthing parents and all healthcare providers in New Zealand

This “How to treat” has been endorsed by the RNZCGP and has been approved for up to 1 credit for continuing professional development purposes (1 credit per learning hour). To claim your CPD credits, complete the assessment at the end of this page, then log in to your Te Whanake dashboard and record this activity under the appropriate learning category.

The College of Nurses Aotearoa (NZ) has endorsed this “How to treat” for 1 hour of professional development following completion of the assessment at the end of this page (CNA107).

At the end of this course, you should be able to:

-

Describe recent changes to ACC coverage of maternal birth injuries

-

Discuss how to diagnose maternal birth injuries in primary care

-

Discuss treatment and support options available for maternal birth injuries

This How to Treat assists with the development of the following domains of competence in the general practice curriculum:

- Domain 1: Communication

- Domain 2: Clinical expertise

- Domain 3: Professionalism

- Domain 4: Scholarship

- Domain 5: Context of general practice

Maternity care in New Zealand includes free and partially funded healthcare services, with the primary maternity services delivered by lead maternity carers. Increased awareness in the early 2020s highlighted the difficulties birthing parents experienced accessing some maternity care, especially if they sustained injuries during the delivery. Public waiting lists for postpartum care in some areas were extremely long, resulting in months of delay in receiving specific treatments, such as pelvic health physiotherapy.

In December 2021, the Accident Compensation (Maternal Birth Injury and Other Matters) Amendment Act 2022 was introduced to parliament by then Minister for ACC Carmel Sepuloni. It proceeded through select committee, public consultation, and passed its final approval in September 2022.

Effective 1 October 2022, Section 25 of the Accident Compensation Act 2021 was amended to enable a new definition of the term “accident”: “An application of a force or resistance internal to the human body at any time from the onset of labour to the completion of delivery that results in an injury described in Schedule 3A to a person who gives birth.”

Schedule 3A was added to describe the injuries that, as of 1 October 2022, are considered birthing injuries and may be covered by ACC (Panel 1). This is a significant change to ACC coverage and is intended to improve equity of access to ACC funded care to enable earlier targeted healthcare and support for birthing parents.

An important point to note is that the act is not retrospective – that is, ACC coverage for the listed maternal birth injuries is only for birthing parents who give birth on or after 1 October 2022. Some injuries prior to this may have been covered under the separate treatment injury process. However, this process was limited in its coverage. Injuries to pēpi (babies) which may happen during labour or delivery have not been included in this change, but treatment injury cover remains an option for them.

- Anterior vaginal wall prolapse, posterior vaginal wall prolapse, or uterine/apical prolapse

- Coccyx fracture, subluxation or dislocation

- Levator ani muscle avulsion

- Obstetric anal sphincter injury tears, or tears to the perineum, labia, vagina, vulva, clitoris, cervix, rectum, anus or urethra

- Obstetric fistula (including vesicovaginal, colovaginal and ureterovaginal)

- Obstetric haematoma of pelvis

- Postpartum uterine inversion

- Pubic ramus fracture

- Pudendal neuropathy

- Ruptured uterus during labour

- Symphysis pubis joint capsule or ligament tear

How many birthing parents in Aotearoa New Zealand will now qualify for ACC funded care for maternal birth injuries?

Out of the approximately 60,000 people giving birth each year in New Zealand, about 30 per cent will have a caesarean section delivery (18,000). That leaves 70 per cent giving birth via spontaneous or instrumental vaginal delivery (42,000). Considering that up to 85 per cent of people who give birth vaginally sustain perineal trauma, it is estimated that up to 35,700 people per year will qualify for ACC funding for perineal tears alone.

These figures exclude the other birthing injuries also covered by ACC. Some of these injuries occur concurrently; some occur independently of each other.

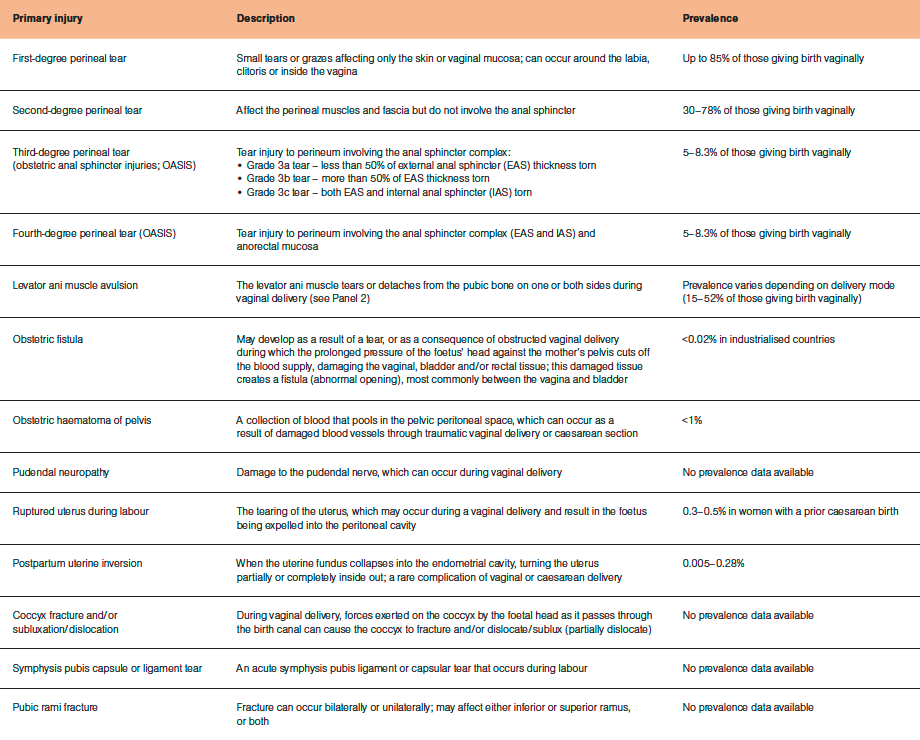

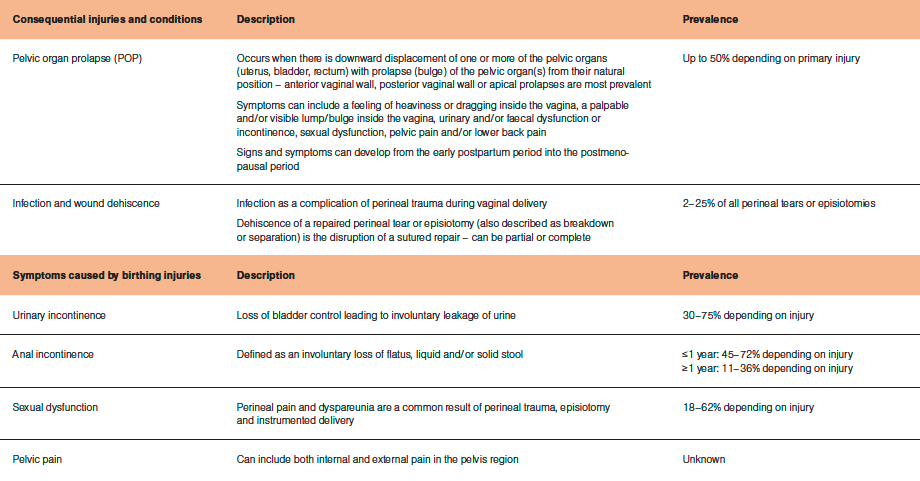

The table provides a summary of the primary maternal birth injuries and their prevalence. Consequential injuries are also summarised.

A proportion of these injuries will be diagnosed and treated immediately in the hospital setting, such as uterine inversion, ruptured uterus, obstetric haematoma and obstetric fistula.

Other injuries will be noted to have occurred but may or may not be registered with ACC at the time of birth due to several factors. Injuries in this category include tears to the perineum, pudendal neuropathy, symphysis pubis dysfunctions, coccyx dysfunctions and pubic ramus fracture. Diagnosis of levator ani muscle avulsions take six to 12 months to confirm as there may be healing of partial avulsions (Panel 2 – see below).

There are also consequential injuries of the primary injury (listed above) to consider, such as pelvic organ prolapse, infection and wound dehiscence. Symptoms of primary birthing injuries can include urinary and anal incontinence, pelvic pain and sexual dysfunction. While these symptoms alone are not considered to be injuries, they are caused by the primary injury and therefore receive coverage.

Depending on the birthing injury, ACC registration of most injuries can be completed by an obstetrician, gynaecologist, colorectal surgeon, GP, nurse practitioner, registered nurse or pelvic health physiotherapist. Midwives can only register perineal tears. Coccyx and symphysis pubis injuries can be registered by musculoskeletal physiotherapists, osteopaths or chiropractors.

See the ‘Maternal birth injuries’ page on the ACC website (acc.co.nz/for-providers/maternal-birth-injuries) for an easy summary sheet of who can register which injury.

As many injuries are not able to be registered by midwives, and birthing parents often do not develop symptoms of injury for weeks or months after birth, GPs and pelvic health physiotherapists need to be prepared to register the injuries.

Normalise, validate and reassure

It can be tempting to discount some of these injuries, such as first-degree tears, as being inconsequential. While this assumption may be true for many birthing parents, for some, these injuries can lead to ongoing scarring, perineal pain, infection and dyspareunia (painful penetrative intercourse). They can also have consequential injuries, such as pelvic organ prolapse, incontinence, or an occult injury to the deep pelvic floor muscles – a levator ani avulsion.

For many birthing parents, there is considerable embarrassment and shame associated with birthing injuries. There can also be a feeling of failure in their ability to have the “perfect normal” birth. The process of delivery and the possible trauma associated with it can affect the birthing parent mentally as well as physically. This can lead to the possibility of post-traumatic stress disorder associated with a difficult birthing process. The injuries can also impact the birthing parent’s ability to bond and care for their newborn baby.

Parents may not realise that while it is common to have birthing injuries, it is not normal to have to suffer with these injuries. Most of the injuries and symptoms are treatable with high success rates with conservative therapy, such as pelvic health physiotherapy.

Screen for injuries at every visit

Research shows that unless asked, patients will not volunteer that they have pelvic health issues. Customer interviews completed by ACC also indicate that according to birthing parents, the six-week postpartum check-up at their GP is very focused on the baby and not on the birthing parent. The parent can feel alone, confused, upset and lost about the changes to their body and the longer-term consequences.

Therefore, at each postpartum visit by the birthing parent, it is recommended that all health professionals screen for birthing injuries and their consequential symptoms. Screening can be quickly incorporated into standard clinical practice in such a way that the birthing parent feels listened to and cared for.

Screening questions to ask are shown in the easy-to-use flow diagram, which is also available for download (tinyurl.com/MBI-screening). There is also a version for patients to read while in waiting rooms, Plunket, gyms, etc.

If the birthing parent complains of any symptoms of birthing injuries, an internal vaginal assessment will assist in the diagnosis of injuries and allow any further registration of new injury codes with ACC. This will ensure the birthing parent is covered for as long as the covered injury causes them to need ongoing support. This may be for the rest of their life as the effects of the injury become apparent over time. Confirmation of the degree of perineal tear, presence of prolapse, and assessment of levator ani muscles (Panel 2) can all be completed during the vaginal examination.

At this stage, referral onwards to a pelvic health physiotherapist is also indicated as it is the internationally recommended conservative treatment for most birthing injuries.1–6 Go to pelvichealthdirectory.co.nz to find a pelvic health physiotherapist in your region.

Maternal birth injury screening questions for health professionals – download from drmelissadavidson.com/resources-mbi-screening-tool-optin

What is levator ani muscle avulsion?

The levator ani muscle stretches up to 320 per cent during a normal vaginal delivery. The anterior fibres at the insertion into the pubic bone stretch the most, and this is where avulsions occur.

Known risk factors for avulsion are maternal age (>35 years), high BMI (>35kg/m2), parity (first vaginal delivery has highest risk), height of mother (4kg), length of second stage of labour (more than two hours), third or fourth-degree perineal tear (OASIS), internal vaginal tear and mode of delivery.7

Incidence rates depend on mode of delivery:

- caesarean section – 1 per cent (after trial of vacuum or forceps)

- spontaneous vaginal delivery – 15 per cent

- vacuum delivery – 21 per cent

- forceps delivery – 52 per cent.

A unilateral avulsion (right side is more common than left) is more likely to occur with spontaneous vaginal delivery and vacuum delivery. With forceps delivery, there is equal chance of unilateral or bilateral avulsion.8

How is it diagnosed?

Diagnosis of avulsion occurs clinically using palpation or high-tech imaging (MRI or three-dimensional transperineal ultrasound – see images below).9 High-tech imaging is only indicated if the gynaecologist determines imaging may assist with surgical decision-making. ACC accepts the clinical diagnosis of avulsion from clinicians experienced in palpation, including pelvic health physiotherapists, GPs and gynaecologists.

The combination of two clinical palpation measurements gives the best reliability for diagnosis:10

- The first measure is confirmation of muscle insertion into either side of the urethra during contraction.

- The second measure is the width between levator ani muscle insertion sites into the pubic bone during contraction.

Pelvic health physiotherapists receive specific training on this assessment technique as part of their training in internal examinations. If you are unsure whether an avulsion is present or not, refer to a pelvic health physiotherapist for a second opinion.

In the initial postpartum period, avulsions can be difficult to diagnose. Some avulsions that appear to be full on the initial assessment are partial and repair within six to 12 months postpartum.11 Regular assessment over that time frame is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

How is it managed?

If the birthing parent has ongoing symptoms after four to six months of conservative treatment (eg, pelvic health physiotherapy), referral onwards to a gynaecologist for ongoing management may be indicated. Currently, there is no surgical repair for levator ani avulsions.

Three-dimensional transperineal ultrasound showing, from left to right: intact levator ani muscles, right levator ani avulsion, bilateral levator ani avulsion. Arrows indicate location of levator ani muscles; dots indicate where muscles should be

Alongside the physical damage that birthing injuries can cause, a traumatic birth can have a devastating psychological effect on a birthing parent and their whānau. The birthing process, the changes to their body, the demands of a newborn baby and hormonal changes can have a significant negative effect. Ensuring the birthing parent has support in place to support them physically and mentally is vital to ensure a healthy parent and whānau.

ACC also funds traditional rongoā Māori healing services as a rehabilitation option. This is part of ACC’s kaupapa Māori health service pathway, which aims to provide culturally appropriate care to birthing parents and whānau. These services include mirimiri (bodywork), whitiwhiti kōrero (support and advice) and karakia (prayer). More information on this rehabilitation option is available on the ACC website (tinyurl.com/ACC-rongoaa)

With these ACC changes, thousands of birthing parents throughout New Zealand will now be able to access funded care that was not previously available. They will no longer have to suffer in silence – embarrassed, shamed and socially isolated. They will no longer have to fear relationships and families breaking up due to the damage that birthing injuries have caused to their physical and mental health.

Funding of care for these injuries through ACC will result in Jessica, who cannot work due to faecal incontinence, returning to the work she loves. It will enable Marama, who had withdrawn from rugby due to pelvic organ prolapses and urinary incontinence, to return to the sport she enjoyed. And Charlie will now be able to achieve her goal of having another baby after being too fearful of intercourse due to her perineal scarring.

- Ask the screening questions at postpartum check-ups – or during any future consultations since symptoms may not occur immediately.

- Refer birthing parents with injuries to pelvic health professionals.

- Remind your patients to keep a copy of their delivery notes to support future claims for consequential injuries that may not show symptoms until many years later.

- ACC. Maternal birth injuries. acc.co.nz/for-providers/maternal-birth-injuries

- Birth Trauma Aotearoa. birthtraumaaotearoa.org.nz

- Continence NZ. continence.org.nz

- Pelvic Health Directory. Find a pelvic health professional. pelvichealthdirectory.co.nz

- Physiotherapy New Zealand. pnz.org.nz

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. ranzcog.edu.au

Your 32-year-old patient recently had her third child. She had a prolapse injury during delivery, which has been covered by ACC. She has begun seeing a women’s health physiotherapist, which is helping with recovery, but it is a slow process. During your consultation, the woman shares that she is feeling very down about the injury – it’s impacting her relationship with her partner who works away a lot, she has little extra support with her three children, and she has discomfort throughout the day. After investigating further, you discover she struggles with sleep, is often anxious (which is new for her) and avoids medical assessments as they remind her of her recent birth.

How can physical injury impact psychological health?

The psychological aspects of birth-related injury are infrequently considered. However, these are often as impactful as the physical injury itself.

Day-to-day distress, helplessness due to loss of bodily function and lifestyle impacts, relationship challenges (particularly regarding intimacy), challenges bonding with baby, shame and grief are all common emotional responses to physical birth injury.

Psychological trauma related to negative birth experiences, regardless of injury, affects approximately 35 per cent of birthing people.12 When a physical injury occurs, which can happen for up to 80 per cent of birthing people, it’s highly likely that psychological stress, even trauma, occurs concurrently. Psychological birth trauma (whether related to physical injury or not) can stretch from mild upset to severe psychological harm, including post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

The impacts of birth-related injury reach far beyond the birthing parent. Because of the central role of the mother/birthing parent within the whānau, physical illness or distress for the parent can hold significant negative impacts for pēpi and their developmental outcomes.13

What treatments are available?

Counselling, rongoā Māori and psychological support all prove valuable in a birthing person’s recovery towards wellness. ACC will cover these treatment services if they relate to an approved birth injury claim.

What other care is needed?

Birthing parents and whānau need empathetic and informed diagnoses and care.

Childcare assistance and home help (both covered by ACC) are valuable as they allow the parent to focus on recovery. Peer support is often incredibly helpful, and Aotearoa-focused groups exist for both physical birth injury and psychological distress related to birth. Mybirthstory.org.nz lists support options regarding the psychological impacts of negative birth experiences, both relating to injury and standalone.

This case study, written by Kate Hicks, does not represent an identifiable person

Shame and stigma keep birthing parents silent and are perhaps the most pervasive barriers to treatment and support

A range of barriers specific to birth-related injury occur for birthing parents and their whānau. The nature of birth, as a momentous time in life, compounds these barriers. Overcoming them requires empathetic, open, educated and trauma-informed care.

Lack of knowledge

“I didn’t know this could happen” is a common patient response following injury. This response is often mixed with grief, disbelief and trauma. A lack of knowledge regarding the potential for injury is often a result of an absence of informed consent. Once injury has occurred, consumers often lack information regarding treatment options.

Equity barriers

System-wide racism, ableism and heteronormative structures and attitudes stop people from accessing care, as do workforce shortages as people struggle to find practitioners who they trust. Gaps in knowledge regarding birth injury (for both practitioners and consumers), and delays in diagnosis and treatment, also create barriers to care and thus impact on patient wellbeing.

Attitudinal barriers

When expressing pain, discomfort or distress, birthing parents are often met with dismissive and harmful attitudes. Examples are: “At least baby is healthy,” “What did you expect? It’s birth,” and “That’s just normal.” These attitudes can come from anyone – from healthcare professionals or friends and whānau.

Shame and stigma

Shame and stigma keep birthing parents silent and are perhaps the most pervasive barriers to treatment and support.

Panel provided by Kate Hicks

Melissa Davidson (PhD) is the only specialist physiotherapist in pelvic health registered with the Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand and is the current president of the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Pelvic and Women’s Health. Dr Melissa Davidson maintains a clinical caseload and teaches pelvic health to health professionals. She can be reached at melissadavidson.org (patient information) or drmelissadavidson.com (pelvic health training).

Kate Hicks is founder and chief executive of Birth Trauma Aotearoa, a consumer-focused charitable trust.

Dr Davidson and Ms Hicks are on ACC’s Expert Advisory Group for Maternal Birth Injuries, an external group formed to provide sector advice on the extension of coverage.

This 10-question multiple-choice assessment is designed to demonstrate that the provided educational reading has been effective in allowing you to meet the learning objectives of this course. Write down your answers to these questions.

1. List three injuries now covered by ACC funding as maternal birth injuries.

2. Which statement regarding eligibility for coverage under the Accident Compensation (Maternal Birth Injury and Other Matters) Amendment Act 2022 is correct?

a. For those who gave birth before 1 October 2022, only consequential injuries registered on or after 1 October 2022 may be covered

b. For those who gave birth on or after 1 October 2022, injuries registered at the time of birth or any time postpartum may be covered

c. For those who gave birth on or after 1 October 2022, only injuries registered at the time of birth may be covered

d. For those who gave birth on or after 1 October 2022, only injuries registered within one year of birth may be covered

e. Injuries registered at the time of birth or any time postpartum may be covered, regardless of when the person gave birth

3. What is a tear injury affecting the perineal muscles and fascia but not involving the anal sphincter?

a. First-degree perineal tear

b. Second-degree perineal tear

c. Third-degree perineal tear (OASIS)

d. Fourth-degree perineal tear (OASIS)

4. Which statement regarding levator ani muscle avulsions is correct?

a. ACC only accepts the clinical diagnosis of avulsion if imaging has been performed

b. Diagnosis of levator ani muscle avulsion can take up to 12 months to confirm

c. Left unilateral avulsions are more common than right unilateral avulsions

d. The risk of levator ani muscle avulsion increases with increasing vaginal parity (number of vaginal births)

5. Most people with pelvic health issues due to maternal birth injuries will bring this up in postpartum consultations. True or False?

a. True

b. False

6. Symptoms of birthing injuries are also eligible for ACC coverage. True or False?

a. True

b. False

7. What symptoms or consequences of maternal birth injuries should you screen for at each postpartum check-up (and during future consultations)?

a. Anal and urinary incontinence

b. Pelvic organ prolapse

c. Pelvic pain and sexual dysfunction

d. All of the above

8. What is the best course of action for most maternal birth injuries diagnosed in primary care?

a. Reassurance that the symptoms are normal and will improve with time

b. Referral onwards to a gynaecologist

c. Referral onwards to a pelvic health physiotherapist

9. Which TWO statements regarding maternal birth injuries and their psychological effects are correct?

a. Counselling, rongoā Māori and psychological support are covered by ACC if they relate to an approved birth injury claim

b. Maternal birth injuries and their psychological effects do not pose significant negative impacts for pēpi

c. Psychological distress relating to birth injury is rarely as impactful as the physical injury

d. When a physical birth injury occurs, it is highly likely that psychological distress will occur

10. Name one traditional rongoā Māori healing service also covered by ACC as a rehabilitation option.

Write down your answers to these questions. Then, to check your answers and record your score, click here.

You can use the Capture button below to record your time spent reading and your answers to the following learning reflection questions, which align with Te Whanake reflection requirements (answer three or more):

- What were the key learnings from this activity?

- How does what you learnt benefit you, or why do you appreciate the learning?

- If you apply your learning, what are the benefits or implications for others?

- Think of a situation where you could apply this learning. What would you do differently now?

- If an opportunity to apply this learning comes up in the future, what measures can be taken to ensure the learning is applied?

- Can you think of any different ways you could apply this learning?

- Are there any skills you need to develop to apply this learning effectively?

We're publishing this article as a FREE READ so it is FREE to read and EASY to share more widely. Please support us and our primary care education resources – subscribe here

1. Woodley SJ, Boyle R, Cody JD, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;12:CD007471.

2. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein AJ (eds). Incontinence, 6th edition. Bristol, UK: International Continence Society; 2017.

3. Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay-Smith EJC. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;10:CD005654.

4. Hagen S, Stark D, Glazener C, et al. Individualised pelvic floor muscle training in women with pelvic organ prolapse (POPPY): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383(9919):796–806.

5. Hagen S, Glazener C, McClurg D, et al. Pelvic floor muscle training for secondary prevention of pelvic organ prolapse (PREVPROL): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389(10067):393–402.

6. Ferreira CH, Dwyer PL, Davidson M, et al. Does pelvic floor muscle training improve female sexual function? A systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 2015;26(12):1735–50.

7. Davidson MJ. Investigation of pelvic floor muscle properties during pregnancy and post-partum [doctoral thesis]. University of Auckland; 2020. researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/52843

8. Rusavy Z, Paymova L, Kozerovsky M, et al. Levator ani avulsion: a systematic evidence review (LASER). BJOG 2022;129(4):517–28.

9. Dietz HP, Bernardo MJ, Kirby A, Shek KL. Minimal criteria for the diagnosis of avulsion of the puborectalis muscle by tomographic ultrasound. Int Urogynecol J 2011;22(6):699–704.

10. Kruger JA, Dietz HP, Budgett SC, Dumoulin CL. Comparison between transperineal ultrasound and digital detection of levator ani trauma. Can we improve the odds? Neurourol Urodyn 2014;33(3):307–11.

11. Halle TK, Staer-Jensen J, Hilde G, et al. Change in prevalence of major levator ani muscle defects from 6 weeks to 1 year postpartum, and maternal and obstetric risk factors: A longitudinal ultrasound study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2020;99(10):1403–10.

12. Creedy DK, Shochet IM, Horsfall J. Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: incidence and contributing factors. Birth 2000;27(2):104–11.

13. Wilkinson C, Gluckman P, Low F. Perinatal mental distress: An under-recognised concern. Auckland, NZ: University of Auckland; 2022. informedfutures.org/perinatal-mental-distress

![Barbara Fountain, editor of New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and Paul Hutchison, GP and senior medical clinician at Tāmaki Health [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20editor%20of%20New%20Zealand%20Doctor%20Rata%20Aotearoa%2C%20and%20Paul%20Hutchison%2C%20GP%20and%20senior%20medical%20clinician%20at%20T%C4%81maki%20Health%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=-HbQ1EYA)

![Lori Peters, NP and advanced health improvement practitioner at Mahitahi Hauora, and Jasper Nacilla, NP at The Terrace Medical Centre in Wellington [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/2.%20Lori%20Peters%2C%20NP%20and%20advanced%20HIP%20at%20Mahitahi%20Hauora%2C%20and%20Jasper%20Nacilla%2C%20NP%20at%20The%20Terrace%20Medical%20Centre%20in%20Wellington%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=sUfbsSF1)

![Ministry of Social Development health and disability coordinator Liz Williams, regional health advisors Mary Mojel and Larah Takarangi, and health and disability coordinators Rebecca Staunton and Myint Than Htut [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/3.%20Ministry%20of%20Social%20Development%27s%20Liz%20Williams%2C%20Mary%20Mojel%2C%20Larah%20Takarangi%2C%20Rebecca%20Staunton%20and%20Myint%20Than%20Htut%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=9ceOujzC)

![Locum GP Helen Fisher, with Te Kuiti Medical Centre NP Bridget Woodney [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/4.%20Locum%20GP%20Helen%20Fisher%2C%20with%20Te%20Kuiti%20Medical%20Centre%20NP%20Bridget%20Woodney%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=TJeODetm)

![Ruby Faulkner, GPEP2, with David Small, GPEP3 from The Doctors Greenmeadows in Napier [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/5.%20Ruby%20Faulkner%2C%20GPEP2%2C%20with%20David%20Small%2C%20GPEP3%20from%20The%20Doctors%20Greenmeadows%20in%20Napier%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=B0u4wsIs)

![Rochelle Langton and Libby Thomas, marketing advisors at the Medical Protection Society [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/6.%20Rochelle%20Langton%20and%20Libby%20Thomas%2C%20marketing%20advisors%20at%20the%20Medical%20Protection%20Society%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=r52_Cf74)

![Specialist GP Lucy Gibberd, medical advisor at MPS, and Zara Bolam, urgent-care specialist at The Nest Health Centre in Inglewood [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/7.%20Specialist%20GP%20Lucy%20Gibberd%2C%20medical%20advisor%20at%20MPS%2C%20and%20Zara%20Bolam%2C%20urgent-care%20specialist%20at%20The%20Nest%20Health%20Centre%20in%20Inglewood%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=z8eVoBU3)

![Olivia Blackmore and Trudee Sharp, NPs at Gore Health Centre, and Gaylene Hastie, NP at Queenstown Medical Centre [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/8.%20Olivia%20Blackmore%20and%20Trudee%20Sharp%2C%20NPs%20at%20Gore%20Health%20Centre%2C%20and%20Gaylene%20Hastie%2C%20NP%20at%20Queenstown%20Medical%20Centre%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=Z6u9d0XH)

![Mary Toloa, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service in Wellington, Mara Coler, clinical pharmacist at Tū Ora Compass Health, and Bhavna Mistry, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/9.%20Mary%20Toloa%2C%20Porirua%20and%20Union%20Community%20Health%20Service%20in%20Wellington%2C%20Mara%20Coler%2C%20T%C5%AB%20Ora%20Compass%20Health%2C%20and%20Bhavna%20Mistry%2C%20PUCHS%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=kpChr0cc)