Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

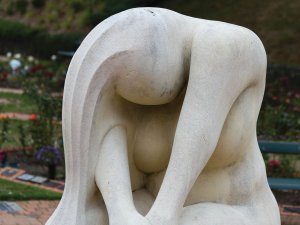

Saying goodbye by phone: Death in lockdown

Saying goodbye by phone: Death in lockdown

Fiona Cassie shares her experience of being unable to say goodbye to her father at his bedside when he died

When your father is frail and 90, your brain, if not your heart, knows you may not have him for much longer.

And that you should always say, “I love you” and give him a big hug every time you say goodbye in case this one is your last.

But that still didn’t make it easier when I was told during lockdown that my father, a plane ride and an island away, had suddenly deteriorated with only a matter of days to live.

And that even if I could make it north in time it would make no difference. As my brother, living just kilometres away from my Dad’s resthome, was also, under the resthome’s lockdown restrictions, unable to hold Dad’s hand for both of us.

Saying goodbye at a deathbed by Zoom and phone hurts. This is despite having last hugged him only two weeks before, and despite that hug following three rollercoaster-but-special weeks with him. He was rushed by ambulance from his home of 25 years to hospital and then discharged two and half weeks later to resthome, hospital-level care.

In between – thanks to the support of the ward team – he managed to return home briefly for a long-planned family gathering to celebrate his 90th birthday.

He appeared to have stabilised and to be settled happily into his new resthome when I gave him that one last hug.

But four weeks after his birthday celebration he returned to his own home one more time in a hearse for an informal but very fond, 10-person funeral. (I have to add it was a 1970s veteran Ford Galaxy hearse – which he specially requested as he loved big American cars with a passion. And the birthday party balloons were still hanging on the walls – it just didn’t seem right to take them down.)

I know as far as lockdown death stories goes mine was on the lucky end of the spectrum.

I had just spent special time with him, and as a family we celebrated his 90 years with lots of cake and laughter.

But it still hurt. And I felt guilt and a surge of empathy for so many people being kept apart from their loved ones for months, and some now even years, through closed borders and lockdowns.

I have to confess that, on occasion, I had sometimes been less than empathetic for those expressing anger at missing a loved one’s death or funeral during the pandemic.

I thought, rather coldly and illogically, that having lost my mum suddenly four years earlier that people needed to accept, like I had to, that even in normal circumstances deaths rarely go to plan.

As a young journalist, I had sat in on a heartbreaking coroner’s inquest where the families of a missing fishing boat crew had their loved ones finally and officially declared dead, their bodies never having been found.

This stood out to me as the toughest grieving scenario – not just not having a body to bury, like the Pike River mine families, but not even having a specific place to mourn them, be it a battlefield, a glacier crevasse or a closed mine.

I’m now a little more human and humble. Knowing that you could have, but can’t, hold the hand of your dying relative or friend due to pandemic restrictions – well, it simply hurts.

While saying goodbye at a distance hurt, the people who cared for my dad in his final days did their very best to ease that farewell for us.

Dad’s last weeks are a very familiar journey for the resthome nursing and GP staff who cared for him.

It is a fresh journey for each family living through it. Which makes the nurses and GPs’ ability to connect and show empathy to those families passing through their care, be it ever so briefly, so important.

I was left with nothing but respect for the professionalism of the nurses and GPs who looked after my dad. They communicated with us, each other and the supporting hospice palliative care team in a way that kept our dad comfortable and us clinically informed and as emotionally connected as possible.

Would I rather have been holding his hand. Yes, of course. But I will be ever thankful for the effort and empathy of others in trying to make up for that gap between our hands.

![Barbara Fountain, editor of New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and Paul Hutchison, GP and senior medical clinician at Tāmaki Health [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20editor%20of%20New%20Zealand%20Doctor%20Rata%20Aotearoa%2C%20and%20Paul%20Hutchison%2C%20GP%20and%20senior%20medical%20clinician%20at%20T%C4%81maki%20Health%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=-HbQ1EYA)

![Lori Peters, NP and advanced health improvement practitioner at Mahitahi Hauora, and Jasper Nacilla, NP at The Terrace Medical Centre in Wellington [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/2.%20Lori%20Peters%2C%20NP%20and%20advanced%20HIP%20at%20Mahitahi%20Hauora%2C%20and%20Jasper%20Nacilla%2C%20NP%20at%20The%20Terrace%20Medical%20Centre%20in%20Wellington%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=sUfbsSF1)

![Ministry of Social Development health and disability coordinator Liz Williams, regional health advisors Mary Mojel and Larah Takarangi, and health and disability coordinators Rebecca Staunton and Myint Than Htut [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/3.%20Ministry%20of%20Social%20Development%27s%20Liz%20Williams%2C%20Mary%20Mojel%2C%20Larah%20Takarangi%2C%20Rebecca%20Staunton%20and%20Myint%20Than%20Htut%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=9ceOujzC)

![Locum GP Helen Fisher, with Te Kuiti Medical Centre NP Bridget Woodney [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/4.%20Locum%20GP%20Helen%20Fisher%2C%20with%20Te%20Kuiti%20Medical%20Centre%20NP%20Bridget%20Woodney%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=TJeODetm)

![Ruby Faulkner, GPEP2, with David Small, GPEP3 from The Doctors Greenmeadows in Napier [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/5.%20Ruby%20Faulkner%2C%20GPEP2%2C%20with%20David%20Small%2C%20GPEP3%20from%20The%20Doctors%20Greenmeadows%20in%20Napier%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=B0u4wsIs)

![Rochelle Langton and Libby Thomas, marketing advisors at the Medical Protection Society [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/6.%20Rochelle%20Langton%20and%20Libby%20Thomas%2C%20marketing%20advisors%20at%20the%20Medical%20Protection%20Society%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=r52_Cf74)

![Specialist GP Lucy Gibberd, medical advisor at MPS, and Zara Bolam, urgent-care specialist at The Nest Health Centre in Inglewood [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/7.%20Specialist%20GP%20Lucy%20Gibberd%2C%20medical%20advisor%20at%20MPS%2C%20and%20Zara%20Bolam%2C%20urgent-care%20specialist%20at%20The%20Nest%20Health%20Centre%20in%20Inglewood%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=z8eVoBU3)

![Olivia Blackmore and Trudee Sharp, NPs at Gore Health Centre, and Gaylene Hastie, NP at Queenstown Medical Centre [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/8.%20Olivia%20Blackmore%20and%20Trudee%20Sharp%2C%20NPs%20at%20Gore%20Health%20Centre%2C%20and%20Gaylene%20Hastie%2C%20NP%20at%20Queenstown%20Medical%20Centre%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=Z6u9d0XH)

![Mary Toloa, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service in Wellington, Mara Coler, clinical pharmacist at Tū Ora Compass Health, and Bhavna Mistry, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/9.%20Mary%20Toloa%2C%20Porirua%20and%20Union%20Community%20Health%20Service%20in%20Wellington%2C%20Mara%20Coler%2C%20T%C5%AB%20Ora%20Compass%20Health%2C%20and%20Bhavna%20Mistry%2C%20PUCHS%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=kpChr0cc)