Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

The answer is more investment in health and welfare – not more rationing of healthcare!

The answer is more investment in health and welfare – not more rationing of healthcare!

from Phil Bagshaw, Sue Bagshaw, Pauline Barnett, Gary Nicholls, Stuart Gowland and Carl Shaw

On 25 February, the New Zealand Medical Journal published an editorial by Saxon Connor, “Is it time to ration access to acute secondary care health services to save the Aotearoa health system?” The editorial was published, with permission on nzdoctor.co.nz. The following letter in response to the editorial is also published with permission

We wish to respond to the article ‘Is it time to ration access to acute secondary care health services to save the Aotearoa health system?’ by Dr Saxon Connor published in the New Zealand Medical Journal and then in New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa on 25 February 2022.

Dr Connor’s arguments are based on one premise “The attempt to meet all the healthcare needs would overwhelm any country’s resources, including the need for other social goods, etc …..”. This is a central mantra of neoliberal philosophy, with its policies for free-market economies and the private provision of public service.1

High levels of unmet need and a creaking system should suggest a need to examine the underlying reasons for both and not rely on a managerialist technical solution.

It is obvious that a major contribution to the high level of unmet need lies in pre-determinants of health such as: poverty, access to primary healthcare, inadequate housing, and poor diet. The other main reason for the creaking health and welfare services, is the thirty years of underinvestment. The objective data from many democratic countries shows that neither healthcare needs nor the required level of adequate funding are overwhelming, as follows:

i.Multi-national European studies have shown that investment policies in health and other welfare services pay large positive fiscal dividends and promotes economic growth (i.e., for every dollar put into health services governments get more dollars back, often referred to as fiscal multipliers).2 Even the International Monetary Fund, a bastion of neoliberalism, which initially disagreed with the results of these studies, has since conceded that such positive fiscal multipliers do result from health and welfare investment.1

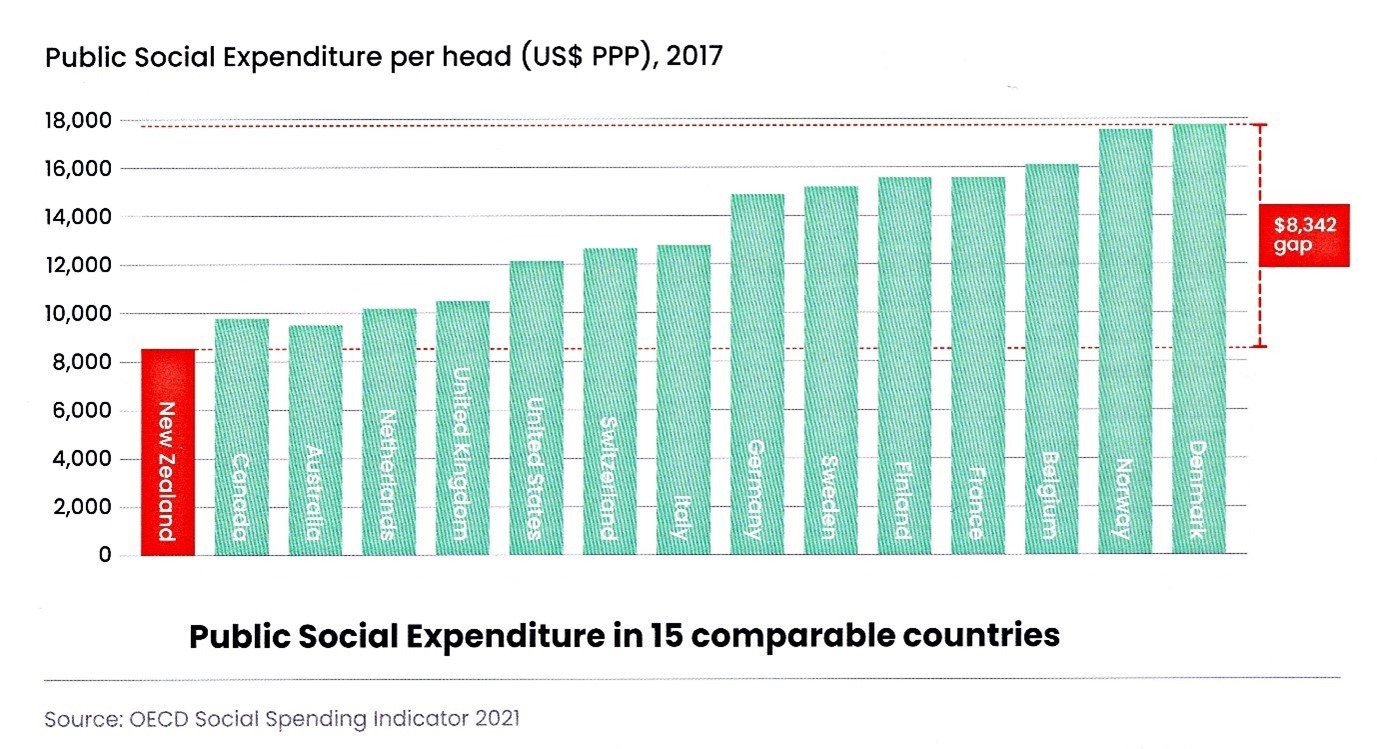

ii.Finland is an exemplar of a country that has shown what can be achieved by a policy of welfare investment.3 By comparison (Table below)4 our own level of social expenditure per capita is much lower and we can afford to do much better.5

The assault on the healthcare system of Aotearoa New Zealand started in earnest with Rogernomics in the early 1990s, and continued through the Core Services Committee and the National Waiting Time Project.6 These steps were needed to prepare the public for the progressive rationing of secondary elective healthcare. There was some isolated and sporadic opposition to these moves from the medical profession.7 However, we neither mounted a coordinated opposition to them through our representative bodies, nor did we effectively highlight the fundamental underlying problems by addressing either the pre-determinant of health or the chronic underfunding of primary and secondary healthcare.

Undoubtedly, the situation has continued to deteriorate because not only has residual neoliberalism continued to eat away at healthcare funding, but it has also fuelled a widening of the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’.8,9 As a consequence, people in the lowest decile groups have suffered the double jeopardy of the worst pre-determinants of health and the poorest access to healthcare services.

So, coming to Dr Connor’s proposal that, as the secondary healthcare system is under massive stress and about to collapse, a potential solution is to extend rationing into acute secondary healthcare. Why again should this be contemplated, rather than a move to an investment model for welfare spending that has been shown to be successful overseas? It is most likely that yet again we, the medical profession, will not advocate en masse on behalf of the public.

If serious rationing of acute secondary services takes off rapidly here, as happened before with elective healthcare, we are likely to end up with a USA-type healthcare system, that is heavily privatized and inefficient, and where: the wealthiest 20% have some of the best healthcare in the world; middle America live in dread of having a major acute or chronic illness and thereby needing to declare bankruptcy; and a poor, uninsured 27.5 million people have almost no access to healthcare.10 It is easy to see how such a dystopian scenario is unlikely to motivate doctors like ourselves who can afford to pay for private healthcare but would be a persistent nightmare for many other people.

The real question is not ‘whether it is time to ration acute secondary care?’ It is instead ‘when will the medical profession wake from its slumbers and begin advocating for the changes in health policies for adequate welfare funding to achieve the goal of equity of health outcomes for all the people we serve?’.

-

Barnett P, Bagshaw P. Neoliberalism: what it is, how it affects health and what to do about it. NZ Med J. 2020;133(1512):76-84.

-

Reeves A, Basu S, McKee M, et al. Does investment in the health sector promote or inhibit economic growth? Global Health. 2013 Sep 23;9:43.

-

Keskimaki I, Tynkkynen L-K, Reissell E, et al. Finland. Health system review. Health Systems in Transition Vol. 21; No. 2; 2019. Accessed at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/327538/HiT-21-2-2019-eng.pdf?sequence=7&isAllowed=y

-

Creating Solutions Te Ara Whai Tika A roadmap to health equity 2040. Co-hosted by Association of Salaried Medical Specialists & Canterbury Charity Hospital Trust. July 2021. (Figure 7, page 40) Accessed at: https://issuu.com/associationofsalariedmedicalspecialists/docs/asms-creating-solutions-fa-web_-_final

-

Keene L, Bagshaw P, Nicholls MG, et al. Funding New Zealand's public healthcare system: time for an honest appraisal and public debate. NZ Med J. 2016;129(1435):10-20.

-

Gauld R, Derrett S. Solving the surgical waiting list problem? New Zealand’s ‘booking system’. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 2000;15(4):259-72.

-

Hornblow A. New Zealand’s health reforms: a clash of cultures. BMJ 1997;314(7098):1892-4.

-

Marcetic B. New Zealand’s Neoliberal Drift. Jacobin Magazine. 2017. Accessed at: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/03/new-zealand-neoliberalism-inequality-welfare-state-tax-haven/

-

Rashbrooke M, Rashbrooke E, Chin A. Wealth inequality in New Zealand. An analysis of the 2014-15 and 2017-18 net worth modules in the Household Economic Survey. Working Paper 21/10 2021. Victoria University of Wellington. Accessed at: https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/1935430/WP-21-10-wealth-inequality-in-New-Zealand.pdf

-

Tikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, et al. The Commonwealth Fund. International Health Care System Profiles. United States. 5th June 2020. Accessed at https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/united-states

![Barbara Fountain, editor of New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and Paul Hutchison, GP and senior medical clinician at Tāmaki Health [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20editor%20of%20New%20Zealand%20Doctor%20Rata%20Aotearoa%2C%20and%20Paul%20Hutchison%2C%20GP%20and%20senior%20medical%20clinician%20at%20T%C4%81maki%20Health%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=-HbQ1EYA)

![Lori Peters, NP and advanced health improvement practitioner at Mahitahi Hauora, and Jasper Nacilla, NP at The Terrace Medical Centre in Wellington [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/2.%20Lori%20Peters%2C%20NP%20and%20advanced%20HIP%20at%20Mahitahi%20Hauora%2C%20and%20Jasper%20Nacilla%2C%20NP%20at%20The%20Terrace%20Medical%20Centre%20in%20Wellington%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=sUfbsSF1)

![Ministry of Social Development health and disability coordinator Liz Williams, regional health advisors Mary Mojel and Larah Takarangi, and health and disability coordinators Rebecca Staunton and Myint Than Htut [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/3.%20Ministry%20of%20Social%20Development%27s%20Liz%20Williams%2C%20Mary%20Mojel%2C%20Larah%20Takarangi%2C%20Rebecca%20Staunton%20and%20Myint%20Than%20Htut%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=9ceOujzC)

![Locum GP Helen Fisher, with Te Kuiti Medical Centre NP Bridget Woodney [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/4.%20Locum%20GP%20Helen%20Fisher%2C%20with%20Te%20Kuiti%20Medical%20Centre%20NP%20Bridget%20Woodney%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=TJeODetm)

![Ruby Faulkner, GPEP2, with David Small, GPEP3 from The Doctors Greenmeadows in Napier [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/5.%20Ruby%20Faulkner%2C%20GPEP2%2C%20with%20David%20Small%2C%20GPEP3%20from%20The%20Doctors%20Greenmeadows%20in%20Napier%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=B0u4wsIs)

![Rochelle Langton and Libby Thomas, marketing advisors at the Medical Protection Society [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/6.%20Rochelle%20Langton%20and%20Libby%20Thomas%2C%20marketing%20advisors%20at%20the%20Medical%20Protection%20Society%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=r52_Cf74)

![Specialist GP Lucy Gibberd, medical advisor at MPS, and Zara Bolam, urgent-care specialist at The Nest Health Centre in Inglewood [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/7.%20Specialist%20GP%20Lucy%20Gibberd%2C%20medical%20advisor%20at%20MPS%2C%20and%20Zara%20Bolam%2C%20urgent-care%20specialist%20at%20The%20Nest%20Health%20Centre%20in%20Inglewood%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=z8eVoBU3)

![Olivia Blackmore and Trudee Sharp, NPs at Gore Health Centre, and Gaylene Hastie, NP at Queenstown Medical Centre [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/8.%20Olivia%20Blackmore%20and%20Trudee%20Sharp%2C%20NPs%20at%20Gore%20Health%20Centre%2C%20and%20Gaylene%20Hastie%2C%20NP%20at%20Queenstown%20Medical%20Centre%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=Z6u9d0XH)

![Mary Toloa, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service in Wellington, Mara Coler, clinical pharmacist at Tū Ora Compass Health, and Bhavna Mistry, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/9.%20Mary%20Toloa%2C%20Porirua%20and%20Union%20Community%20Health%20Service%20in%20Wellington%2C%20Mara%20Coler%2C%20T%C5%AB%20Ora%20Compass%20Health%2C%20and%20Bhavna%20Mistry%2C%20PUCHS%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=kpChr0cc)