Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

Choose the right words: Misapplication of terms obscures inequities

Choose the right words: Misapplication of terms obscures inequities

Using confusing terms in health documents, such as ‘non-avoidable’, can conceal disparities and undermine efforts towards achieving true health equity, writes Gabrielle Baker

The words we use matter. When working in technical areas, which is usually the case in health services, we must be precise with our terminology, or we are at risk of causing harm. Yet equally, when using terms that have different meanings outside our small sphere, especially in documents meant for use by people not trained in – for example – epidemiology, it looks like jargon, and we risk being misunderstood or creating harm of another type.

Last week, I spent too long asking Google what “non-avoidable” means. At first, my search engine refused to comply with my request – giving me what you might call a common-use alternative: “unavoidable”.

Unavoidable means inevitable, bound to happen, beyond our control.

So, I abandoned that search and went to Google Scholar, which (and we must all know this intuitively) most people wouldn’t bother with if they were just casually reading something and wanted to know what it meant.

I’ve spent years trying to decipher what government publications are telling us about Māori health. So, I am highly motivated to understand why Te Whatu Ora published a report attributing a sizeable proportion of the (inequitable) difference of life expectancy between Māori and non-Māori/non-Pacific populations to “non-avoidable” causes because it appears to be undoing the hard-fought work to build a broader understanding of health inequities as differences which are “unnecessary and avoidable, but in addition, are considered unfair and unjust”.1

The newly released Aotearoa New Zealand Health Status Report 2023 is meant to “tell a comprehensive story about who we are, how we live, and lifestyle factors influencing health and critical health outcomes”.2 It essentially takes the place of the health-needs assessments that each of the 20 district health boards was required to do under the now-repealed New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000.

Therefore, not unjust and unfair. And, therefore, not inequitable. Gross

The report was developed to inform the development of a New Zealand Health Plan 2024–2027 (which will be published later) but has “many other uses and benefits”. As the report notes, it is non-traditional because it doesn’t include service user or community perspectives – but both will be included next time. In particular, “information on broader Māori perspectives of health and wellbeing and holistic concepts that are deeply important to Māori is limited”.

It is clear from the report’s introduction that it has other limitations, too. These are mostly related to having to use the data available, even if not perfect (as is the case of ethnicity, with evidence that Māori are systematically undercounted in NHI ethnicity data).3 There are also limitations where data essentially doesn’t exist (as is the case with data about the health of tāngata whaikaha/ disabled people).

In the early pages of the report, the emphasis appears to be on describing inequities in health outcomes between population groups. In doing so, the report repeats the Ministry of Health definition of equity: “In Aotearoa New Zealand, people have differences in health that are not only avoidable but unfair and unjust. Equity recognises different people with different levels of advantage require different approaches and resources to get equitable health outcomes.”4

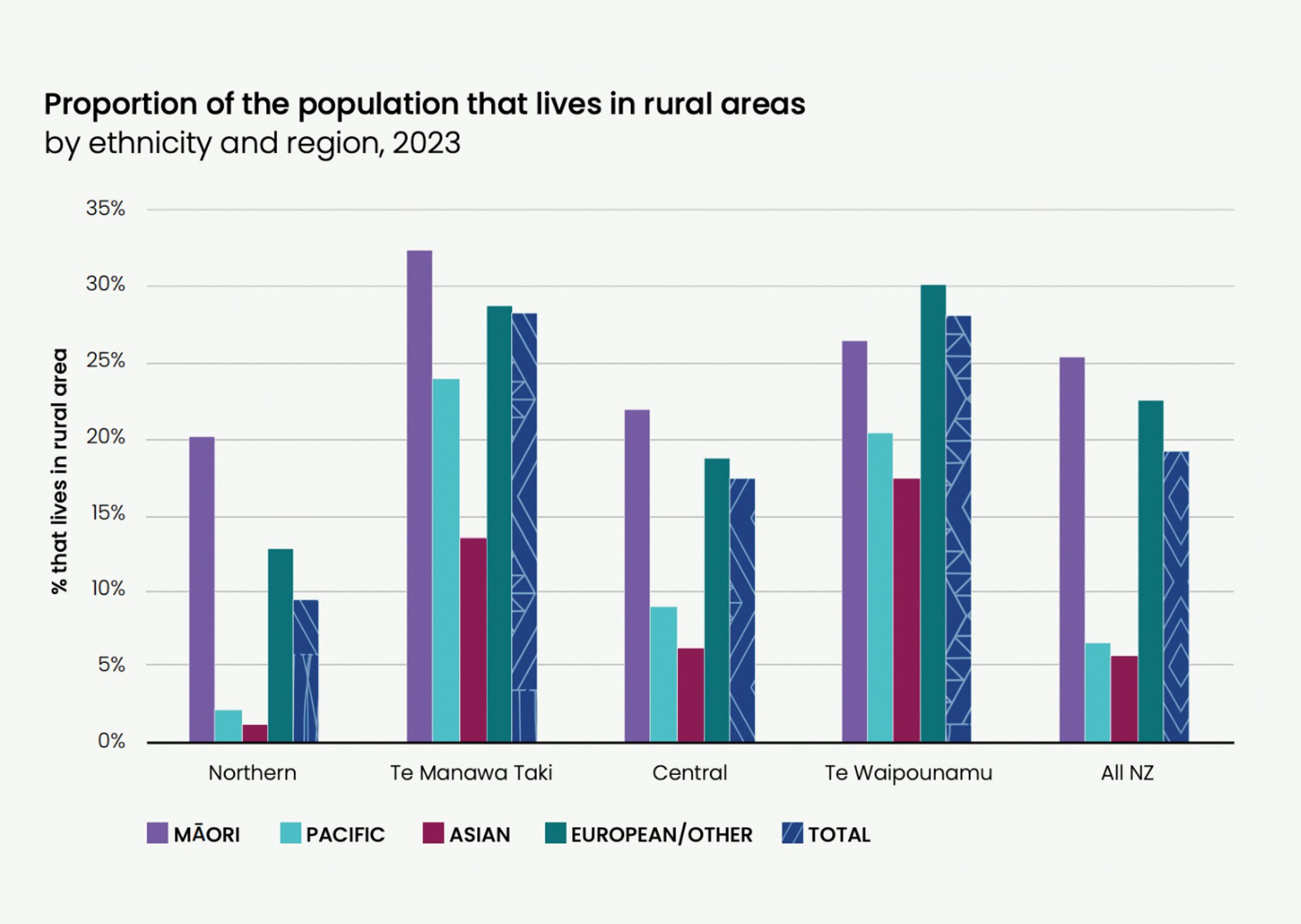

As you go through the report, you can see helpful, clearly presented, information on all sorts of topics. I was especially taken with the data on rurality. We are often told that rural populations have inequities compared with more urban populations, and sometimes, this feels like it is a tactic to say ethnic inequities aren’t that bad because inequities affect other people, too. But the data emphasises an intersection between rurality and ethnicity – with Māori making up the highest proportion of the rural population of any ethnic group in three of the four regions of Aotearoa. Without data, we can only imagine the additional impacts of rurality for Māori with lived experience of disability.

But when I got to the life expectancy section, I was stopped in my tracks. It is not news that the differences in life expectancy between Māori and non-Māori/non-Pacific populations are unfair and unjust, but it continues to be awful. The report quantifies this as Māori women dying, on average, seven years earlier than European/Other women and Māori men eight years earlier than European/ Other men.

The report digs into this further by providing an overview of the factors contributing to the life expectancy gap between Māori and Pacific people compared with non-Māori/non-Pacific people.

These factors are split into four groups: amenable only, preventable only, amenable and preventable, and (gasp) non-avoidable. Between one and three years of the life expectancy gap for Māori is classed as non-avoidable (depending on what part of Aotearoa you live).

The terms amenable and preventable are discussed in the body of the report. Avoidable mortality is deaths occurring in those aged 0–74 years (excluding stillbirths) that could potentially have been avoided. Prevention includes successful public health promotion such as Smokefree legislation, alcohol harm reduction and injury prevention. But non-avoidable? What is that? The only description is in the section on ICD-10 codes5 where non-avoidable is “all other deaths not listed in the above in all age groups”.

The problem I have with this, if it wasn’t immediately obvious, is that it looks like the report and Te Whatu Ora are positioning a chunk of the differences in life expectancy between Māori and non-Māori/non-Pacific populations as beyond anyone’s control. Therefore, not unjust and unfair. And, therefore, not inequitable. Gross.

By not clearly explaining what is meant by nonavoidable, the report opens itself up to misuse. It’s going to be easy for those who are uncomfortable with a rights-based approach, eliminating racism, or focusing on inequity to use this kind of analysis to say, “Well, of course, some of this is going to happen anyway, so we do not need to invest in reducing the gap to zero, just a bit of improvement is probably all we can do.” Or “We can’t possibly be monitored for our progress in achieving equity when so much of the difference is inevitable.”

Frankly, I couldn’t find an easily understood explanation of the term “non-avoidable”, even with my more focused searching. This says to me there were never grounds to use the term without a proper definition, in the glossary at the very least. It is incredibly disappointing. The solution would obviously be to find a more appropriate framing of what is currently classed as “non-avoidable”. I think the authors are getting at factors that aren’t directly addressed by the limited range of interventions available to the health system. Being clearer on this would have provided an opportunity to call for the whole of government working to address the determinants of health. Instead, we have the potential for it to be a (weak) excuse for underinvestment and underperformance. Coming at a time when names of organisations are being carefully changed to be “acceptable” in the current climate, such loose use of technical language is especially disappointing. Hopefully, it is not non-avoidable in the future.

Gabrielle Baker (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kuri) is an independent health policy consultant

- Whitehead M. 1992. The concepts and principles of equity and health. International Journal of Health Services 22:429–445.

- https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/publications/health-status-report/

- Harris, R, et al. We still don’t count: the under-counting and under-representation of Māori in health and disability sector data. New Zealand Medical Journal (2022).

- Available on the Ministry of Health website: https://www.health.govt.nz/about-ministry/what-we-do/achieving-equity#:~:text=World%20Health%20Organization.-,The%20definition,to%20get%20equitable%20health%20outcomes

- If you want to know more about this international classification system for diseases, you can visit the WHO website: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/classification-of-diseases

![Barbara Fountain, editor of New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and Paul Hutchison, GP and senior medical clinician at Tāmaki Health [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20editor%20of%20New%20Zealand%20Doctor%20Rata%20Aotearoa%2C%20and%20Paul%20Hutchison%2C%20GP%20and%20senior%20medical%20clinician%20at%20T%C4%81maki%20Health%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=-HbQ1EYA)

![Lori Peters, NP and advanced health improvement practitioner at Mahitahi Hauora, and Jasper Nacilla, NP at The Terrace Medical Centre in Wellington [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/2.%20Lori%20Peters%2C%20NP%20and%20advanced%20HIP%20at%20Mahitahi%20Hauora%2C%20and%20Jasper%20Nacilla%2C%20NP%20at%20The%20Terrace%20Medical%20Centre%20in%20Wellington%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=sUfbsSF1)

![Ministry of Social Development health and disability coordinator Liz Williams, regional health advisors Mary Mojel and Larah Takarangi, and health and disability coordinators Rebecca Staunton and Myint Than Htut [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/3.%20Ministry%20of%20Social%20Development%27s%20Liz%20Williams%2C%20Mary%20Mojel%2C%20Larah%20Takarangi%2C%20Rebecca%20Staunton%20and%20Myint%20Than%20Htut%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=9ceOujzC)

![Locum GP Helen Fisher, with Te Kuiti Medical Centre NP Bridget Woodney [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/4.%20Locum%20GP%20Helen%20Fisher%2C%20with%20Te%20Kuiti%20Medical%20Centre%20NP%20Bridget%20Woodney%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=TJeODetm)

![Ruby Faulkner, GPEP2, with David Small, GPEP3 from The Doctors Greenmeadows in Napier [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/5.%20Ruby%20Faulkner%2C%20GPEP2%2C%20with%20David%20Small%2C%20GPEP3%20from%20The%20Doctors%20Greenmeadows%20in%20Napier%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=B0u4wsIs)

![Rochelle Langton and Libby Thomas, marketing advisors at the Medical Protection Society [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/6.%20Rochelle%20Langton%20and%20Libby%20Thomas%2C%20marketing%20advisors%20at%20the%20Medical%20Protection%20Society%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=r52_Cf74)

![Specialist GP Lucy Gibberd, medical advisor at MPS, and Zara Bolam, urgent-care specialist at The Nest Health Centre in Inglewood [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/7.%20Specialist%20GP%20Lucy%20Gibberd%2C%20medical%20advisor%20at%20MPS%2C%20and%20Zara%20Bolam%2C%20urgent-care%20specialist%20at%20The%20Nest%20Health%20Centre%20in%20Inglewood%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=z8eVoBU3)

![Olivia Blackmore and Trudee Sharp, NPs at Gore Health Centre, and Gaylene Hastie, NP at Queenstown Medical Centre [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/8.%20Olivia%20Blackmore%20and%20Trudee%20Sharp%2C%20NPs%20at%20Gore%20Health%20Centre%2C%20and%20Gaylene%20Hastie%2C%20NP%20at%20Queenstown%20Medical%20Centre%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=Z6u9d0XH)

![Mary Toloa, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service in Wellington, Mara Coler, clinical pharmacist at Tū Ora Compass Health, and Bhavna Mistry, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/9.%20Mary%20Toloa%2C%20Porirua%20and%20Union%20Community%20Health%20Service%20in%20Wellington%2C%20Mara%20Coler%2C%20T%C5%AB%20Ora%20Compass%20Health%2C%20and%20Bhavna%20Mistry%2C%20PUCHS%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=kpChr0cc)