Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

First Rural Health Strategy acknowledges rural people’s higher death rate

First Rural Health Strategy acknowledges rural people’s higher death rate

Time and time again what was happening is that we were seeing strategies developed by urban people in urban areas and then just put out to rural

The country’s first-ever strategy for improving rural health was released last week just as researchers were publicising their findings on the higher death rates of rural compared with urban people.

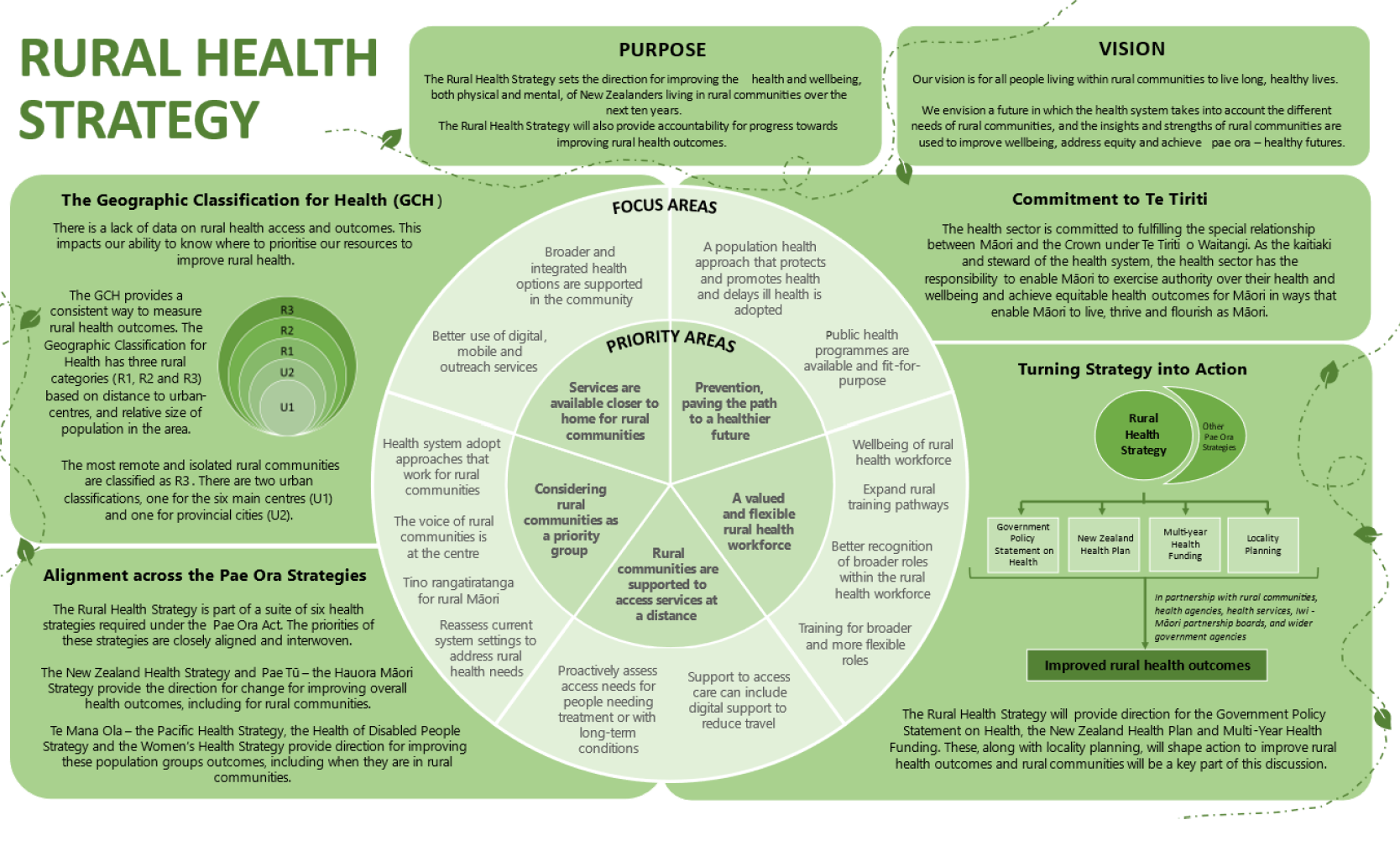

The new 70-page Rural Health Strategy was released last week by health minister Ayesha Verrall alongside the New Zealand Health Strategy and strategies for other priority populations.

On the same day rural researchers led by Garry Nixon of the University of Otago issued a media release on the first study to show consistently higher mortality rates for rural populations.

Hauora Taiwhenua chair and specialist GP Fiona Bolden says the strategy, setting the direction for improving rural health outcomes over the next 10 years, includes “most” of what the rural health network had hoped to see.

“It’s a really good start, seeing this is the first time we’ve had a rural health strategy,” Dr Bolden says.

Rural communities were included as a priority group at the last minute in the health reforms’ Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act 2022.

The network fought to have rural a priority in the legislation and a “for rural by rural” health strategy so there would be government accountability on progress to meeting rural health outcomes, says Dr Bolden.

“Time and time again, what was happening is that we were seeing strategies developed by urban people in urban areas and then just put out to rural.” The strategy’s five priorities, which include workforce and support to access services, are “very sound”.

While not directly addressing the rural health crisis, the strategy points out a “number of areas under a huge amount of pressure”, including access to care, she says.

The strategy acknowledges the work of specialist GP Professor Nixon and collaborators on developing the new Geographic Classification for Health [GCH], noting this provides a “consistent way” to measure rural health outcomes. Also mentioned are the researchers’ recently published findings on the rural mortality gap (J Epidemiol Community Health, online 9 June).

The strategy fails to mention funding, Dr Bolden says, but she expects to see funding and specific actions backing the strategy’s vision to follow in the Government Policy Statement on Health.

This is expected to include action on the network’s key priority of a “valued and flexible rural health workforce” which, she says, means the rural health workforce needs to be paid adequately.

“And there isn’t any mention of adequate pay and funding within this particular strategy document. That’s what I’d hope to see in the government policy statement.”

She also says lacking specific attention in the strategy is the role of rural general practice.

“We know there are huge issues around access to the rural general practice now because of the diminishing workforce.”

Rural general practice teams are crucial at not only providing health prevention and supporting wellbeing but also addressing health needs by treating illness and offering emergency care, says Dr Bolden.

It is not clear, she says, whether the strategy will help address the crisis in rural general practices and rural hospitals “unless we see some very swift action coming out of the government policy statement”.

The strategy document acknowledges the lack of data on rural health access and outcomes and points to the GCH’s new rural categories R1, R2 and R3 as a way of gathering consistent data.

Published last year, the GCH differs from the Stats NZ rural classifications by defining more small towns as rural and by no longer regarding the commuter belts around big cities as rural.

Professor Nixon has said the Stats NZ classifications appear to have masked rural health disparities. Using Stats NZ classifications, analysis showed few differences between rural and urban health outcomes, but using the GCH rural definitions revealed all-cause mortality rates for rural residents were 21 per cent higher than for urban people.

The reclassification was used in the study published in the journal. Analysis of more than 160,000 deaths between 2014 to 2018 found mortality rates are higher in rural areas than major urban areas across all groups under 60, says lead author Professor Nixon, in a media release.

The largest disparities were for people under 30 with mortality rates almost double that of urban centres. Disparities were most evident for injuries and amenable (preventable) deaths and were present for cardiovascular disease.

Co-author, academic and specialist GP Sue Crengle, in the release, adds that although both rural Māori and rural non-Māori have higher mortality rates than their urban peers, the consequences for Māori are greater.

The Rural Health Strategy looked at all-age mortality data for 2018 to 2020 and found rural amenable mortality rates were 20 per cent higher than for urban populations. Rural Māori amenable mortality was around 12 per cent higher than that for urban Māori.

The research found that in 2018 the main causes of amenable mortality in rural communities were ischaemic heart diseases, external causes (including accidents and suicides) and cancer. External causes for males and non-Māori were a higher proportion of deaths in rural communities than urban.

![Barbara Fountain, editor of New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa, and Paul Hutchison, GP and senior medical clinician at Tāmaki Health [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20editor%20of%20New%20Zealand%20Doctor%20Rata%20Aotearoa%2C%20and%20Paul%20Hutchison%2C%20GP%20and%20senior%20medical%20clinician%20at%20T%C4%81maki%20Health%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=-HbQ1EYA)

![Lori Peters, NP and advanced health improvement practitioner at Mahitahi Hauora, and Jasper Nacilla, NP at The Terrace Medical Centre in Wellington [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/2.%20Lori%20Peters%2C%20NP%20and%20advanced%20HIP%20at%20Mahitahi%20Hauora%2C%20and%20Jasper%20Nacilla%2C%20NP%20at%20The%20Terrace%20Medical%20Centre%20in%20Wellington%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=sUfbsSF1)

![Ministry of Social Development health and disability coordinator Liz Williams, regional health advisors Mary Mojel and Larah Takarangi, and health and disability coordinators Rebecca Staunton and Myint Than Htut [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/3.%20Ministry%20of%20Social%20Development%27s%20Liz%20Williams%2C%20Mary%20Mojel%2C%20Larah%20Takarangi%2C%20Rebecca%20Staunton%20and%20Myint%20Than%20Htut%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=9ceOujzC)

![Locum GP Helen Fisher, with Te Kuiti Medical Centre NP Bridget Woodney [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/4.%20Locum%20GP%20Helen%20Fisher%2C%20with%20Te%20Kuiti%20Medical%20Centre%20NP%20Bridget%20Woodney%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=TJeODetm)

![Ruby Faulkner, GPEP2, with David Small, GPEP3 from The Doctors Greenmeadows in Napier [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/5.%20Ruby%20Faulkner%2C%20GPEP2%2C%20with%20David%20Small%2C%20GPEP3%20from%20The%20Doctors%20Greenmeadows%20in%20Napier%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=B0u4wsIs)

![Rochelle Langton and Libby Thomas, marketing advisors at the Medical Protection Society [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/6.%20Rochelle%20Langton%20and%20Libby%20Thomas%2C%20marketing%20advisors%20at%20the%20Medical%20Protection%20Society%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=r52_Cf74)

![Specialist GP Lucy Gibberd, medical advisor at MPS, and Zara Bolam, urgent-care specialist at The Nest Health Centre in Inglewood [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/7.%20Specialist%20GP%20Lucy%20Gibberd%2C%20medical%20advisor%20at%20MPS%2C%20and%20Zara%20Bolam%2C%20urgent-care%20specialist%20at%20The%20Nest%20Health%20Centre%20in%20Inglewood%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=z8eVoBU3)

![Olivia Blackmore and Trudee Sharp, NPs at Gore Health Centre, and Gaylene Hastie, NP at Queenstown Medical Centre [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/8.%20Olivia%20Blackmore%20and%20Trudee%20Sharp%2C%20NPs%20at%20Gore%20Health%20Centre%2C%20and%20Gaylene%20Hastie%2C%20NP%20at%20Queenstown%20Medical%20Centre%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=Z6u9d0XH)

![Mary Toloa, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service in Wellington, Mara Coler, clinical pharmacist at Tū Ora Compass Health, and Bhavna Mistry, specialist GP at Porirua and Union Community Health Service [Image: Simon Maude]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-03/9.%20Mary%20Toloa%2C%20Porirua%20and%20Union%20Community%20Health%20Service%20in%20Wellington%2C%20Mara%20Coler%2C%20T%C5%AB%20Ora%20Compass%20Health%2C%20and%20Bhavna%20Mistry%2C%20PUCHS%20CR%20Simon%20Maude.jpg?itok=kpChr0cc)