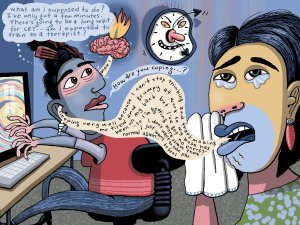

A range of approaches is needed to manage mental health presentations. In this article, specialist GP Sophie Jadwiga Ball describes two tools that can be employed within a GP consultation and provides the evidence-based theory behind their use. She also presents numerous examples to demonstrate how you can apply these tools in practice

Preserving the highly-valued priority of independence

Preserving the highly-valued priority of independence

Health priorities of older adults often include longevity, however health outcomes such as quality of life and independence are often considered to be as important or more important than a long life.1

The majority of older adults would prefer to age at home2 as it allows them to stay in control over their lives, and promotes feelings of purpose, achievement and self-worth. Living at home also allows connection to family, friends, and the community, which is critical for social support and mental wellbeing.

The ability of older adults to live independently can be put at risk by a cardiovascular event or other medical issues such as a fall or breathing difficulties.

Stroke, heart failure and heart attack are associated with poor health status and long-term disability,3 which could lead to loss of independence. Seniors with heart failure who delay seeking care for worsening symptoms, in fear of losing control of their health and independence, are at increased risk of rehospitalisation after discharge.4

Hospitalisation for a medical event, such as a heart attack or stroke, is a risk factor for functional decline (inability to perform the basic tasks of daily living) in older adults.5,6 This can be a ‘deconditioning’ process, leading to dependency after hospitalisation.7

Being able to perform the tasks of daily living is closely linked to living longer, independence and the preservation of quality of life, all of which are key health priorities for seniors.1

Maintenance of functional capacity and independent living is important to consider in clinical decision making for older adults.

76% of heart attacks attended by emergency services occurred in the home and 63% were unwitnessed.8

As a healthcare professional, you can support your older patients’ independence by referring them for a St John Medical Alarm.

Medical alarms (personal emergency response systems) offer the potential to preserve the wellbeing and independence of seniors living at home by enabling timely intervention in case of a cardiovascular event or other health-related emergency. Analysis of an Australia-New Zealand out-of-hospital cardiac arrest registry determined that over one year 76% of heart attacks attended by emergency services occurred in the home and 63% were unwitnessed.8

Timely intervention is important for averting hospitalisation and minimising the need for long-term aged care. Research indicates that the use of a medical alarm by community-dwelling seniors can reduce mortality rates, hospital admissions and inpatient days,9,10 potentially reducing the likelihood of loss of independence.

Although you cannot be there to protect your older patients all the time, a St John Medical Alarm allows your patients to return home knowing they can access expert care whenever they need it. This can instil the confidence to live a full, independent life and to stay at home for longer.

A St John Medical Alarm offers 24/7 response and is the only medical alarm that connects directly to Hato Hone St John. Your patients have access to a FREE trial and referral is straightforward through your Practice Management System via Healthlink or ERMS.

For more information go to stjohnalarms.org.nz/hcp

1. Goyal P, et al. JACC: Advances. 2022;1(3):100070. 2. Aging in place in America. Research Study. PositiveAging Sourcebook. 2018. 3. Matza LS, et al. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:173. 4. Lin CY, et al. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021;20(5):454-63. 5. Covinsky KE, et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-8. 6. Dharmarajan K, et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(3):486-95. 7. Covinsky KE, et al. JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-93. 8. Bray J, et al. Resuscitation. 2022;172:74-83. 9. Ong NWR, et al. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(4):594-601. 10. Roush RE, et al. South Med J. 1995;88(9):917-22.