Respiratory physician Lutz Beckert considers chronic obstructive pulmonary disease management, including the prevention of COPD, the importance of smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation, and the lifesaving potential of addressing treatable traits. He also discusses the logic of inhaler therapy, moving from single therapy to dual and triple therapy when indicated, as well as other aspects of management

Fear of Falling and Risk to Seniors’ Independence

Fear of Falling and Risk to Seniors’ Independence

The majority of seniors report that they want to live at home for as long as possible and that moving from home into age related residential care is one of their major fears.1 However, seniors are at risk of falling and other health-related issues, such as cardiac or respiratory events, which can lead them to losing their independence.

Patients who receive delayed care after a fall at home are more likely to require long-term age related residential care after hospital discharge.

A fall has the potential to cause a significant injury or fracture, and with one in three community-residing seniors aged over 65 experiencing one every year,2 falls pose a serious risk to independence. Moreover, patients who receive delayed care after a fall or other health-related event at home (i.e., a long lie-time) are more likely to require long-term age related residential care after hospital discharge versus those who receive assistance more quickly.3

The threat that falling poses to a senior’s wellbeing and independence is compounded by a post-fall form of anxiety termed fear of falling. Experiencing a fall in the previous year has been demonstrated to be significantly associated with a fear of falling, and the frequency of this fear could be as high as 75% among community-residing seniors who have experienced a recent fall.4

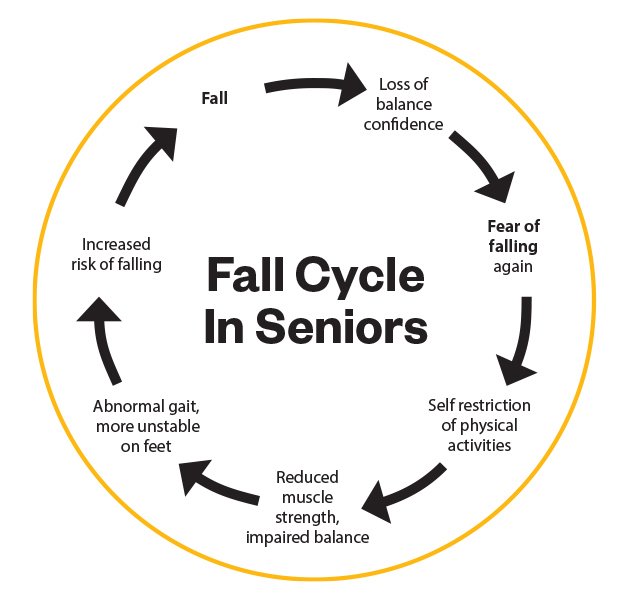

Fear of falling drives the fall cycle. Falls can knock seniors’ confidence in their ability to maintain balance, provoking self-imposed restrictions on their everyday activities at home and in the community which leads to additional decline in physical abilities and further increasing the risk of subsequent falls, injuries, and hospital admission.

A previous fall, and the fear of falling again, can increase the risk of physical frailty and potential falls in older adults. Also, a long lie-time can increase the likelihood of long-term aged related residential care. Understanding these factors should prompt healthcare professionals to take action to support the wellbeing and independence of their senior patients.

One such action could be to recommend the use of a medical alarm. These devices can support the wellbeing and independence of seniors living at home by enabling timely intervention should they experience a fall or other health-related event.

The perceived benefits of medical alarms reported by community-residing seniors include reduced anxiety about falling, increased confidence in performing activities of daily living, and extending the time they are able to remain living at home.5,6

A helpful tool for identifying which of your senior patients is at risk of falling is the Health, Quality, and Safety Commission’s Ask, Assess, Act process. This screens a patient’s risk factors, which include a previous fall and fear of falling again.7

Although it is not practical to watch over your patients all of the time, with a St John Medical Alarm senior patients in your care are able to go home and be and feel safe knowing that they can access help 24/7 if needed, giving them the peace of mind and reassurance to live a full, independent life, and to stay at home for longer.

A St John Medical Alarm, which offers 24/7 response, is the only medical alarm that connects directly to St John. All patients are eligible for a free trial for up to 14 days, and referral is a straightforward process through your Practice Management System via Healthlink or ERMS.

For more information visit stjohnalarms.org.nz/hcp

1. Aging in place in America. Research Study. PositiveAging Sourcebook. 2018. https://www.retirementlivingsourcebook.com/articles/research-study-%E2%80%9Caging-in-place-in-america-%E2%80%9D%C2%9D.

2. Soriano TA, et al. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2(4):545-554.

3. Gurley RJ, et al. NEJM. 1996;334(26):1710-1716.

4. Chen W-C, et al. Medicine. 2021;100(26):e26492.

5. De San Miguel K et al. Australas Journal on Ageing. 2008;27(2):103-105.

6. De San Miguel K, et al. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2017;36(3-4):164-177.

7. Health Quality & Safety Commission New Zealand. https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-work/system-safety/reducing-harm/falls/10-topics/topic-4-addressing-risk-factors-in-an-individualised-care-plan/.